Objects, Installations and Ready-Mades

Since the beginning of the 20th century, the state of contemporary art has resembled the smile of Lewis Carroll’s Cheshire cat: the Cat is gone, the smile is hanging in the air, and you can’t tell whether it’s real or not. An uninitiated viewer often finds the classification ‘contemporary’ art arcane and has few clues with which to understand what exactly constitutes this genre. The only thing that’s clear is that the traditional notion of ‘artistry’ has nothing to do with it.

One famous artist wraps bridges and public buildings in nylon and polypropylene. Another travels around the world tagging museums and galleries with a banana drawing on their walls. Yet another strips naked and impersonates a dog in front of the surprised citizens of Stockholm. People buy expensive tins with “artist’s shit” written on them. The real contents remain unknown. These are the new forms of art that have been discovered in the 20th century. We’ll talk about some of these forms in the next two lectures. We won’t limit ourselves to the confines of Russian art and will revisit some moments in history. We’ll begin with objects and installations.

The word ‘object’ has many meanings. It can refer to a ‘found object’ which the artist has not modified (or only barely), but claimed as his work. The Frenchman Marcel Duchamp is considered to be the pioneer of the genre. A bicycle wheel mounted on a wooden stool, a bottle rack and, of course, a urinal turned upside down, placed on a podium and titled Fountain are some of his readymades. The will of the author is in this case of principal importance. The author is not someone who has crafted something with his own hands or painted a picture, but one who claims: ”This is art, because I, the artist, say so.” In this context, the intention is much more important than the execution. The bottle rack and the urinal are much more than just a bottle rack and a urinal; they boldly manifest the new role of the artist, a new way of presenting an artwork, and a brand new context for the relationship between art and its viewer. This altered 20th century art history and infinitely expanded art’s boundaries.

But apart from ‘found’ objects, intended for other quite different purposes than art, there are also ‘constructed’ objects. These pieces are not artistic gestures, but man-made things. These objects usually inhabit the magical space close to such traditional art forms as painting and sculpture, or less traditional ones like architectural or industrial design. They seem to slip out of these categories, while simultaneously remaining in touch with them, honouring their production techniques, materials, and craft itself.

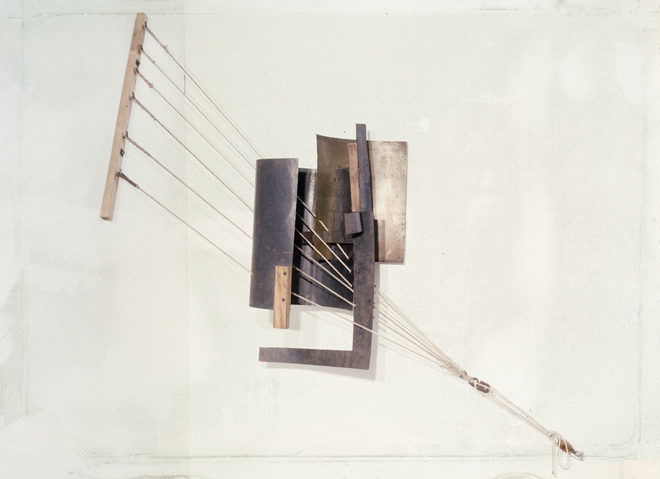

In the history of the Russian Avant-Garde, Vladimir Tatlin is the most well-known creator of such objects, in his counter-reliefs. These were three-dimensional compositions of wood, metal and even glass parts, attached to a board. Tatlin cultivated the ethics of “being true to materials” and loved these materials for their weight and for being “real things”, and he never repaired natural wood defects. Aside from Tatlin, many others were creating this kind of art at the turn of the 1910s to 1920s: David Burlyuk, Ivan Klyun, Ivan Puni, Lev Bruni, Vladimir Baranov-Rossine, and others; while Pablo Picasso was considered the pioneer of “three-dimensional paintings” in the West. And they were indeed three-dimensional pictures – they can hang on a wall, they have a living relationship with painting (in Tatlin’s case, even with Orthodox icons), and they actively conquer space without turning into sculptures. Much later, the French painter Jean Dubuffet would coin the term ‘assemblage’ for such artworks. This could be characterised as a collage with both flat and three-dimensional elements, including either found or purchased ready-made objects.

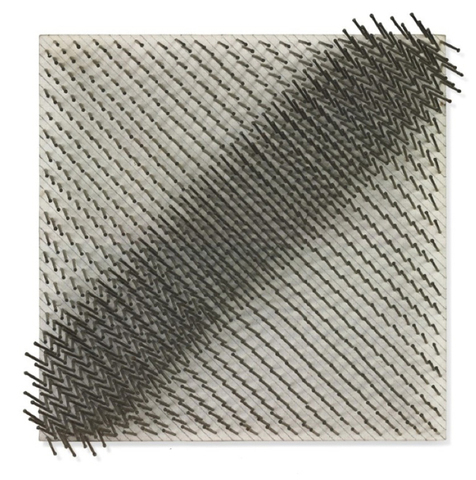

Different elements and materials fuse together in these objects, and this conjunction can result in a variety of meanings and connotations. As with Tatlin’s works, this can appeal to the organic perception of the whole, to both sight and touch. Alternatively, it can playfully destroy the boundaries between art and life. Sometimes materials are used in an uncharacteristic manner. The German artist Günther Uecker makes artworks out of nails, for example. When this creates an abstraction, the nails’ layout mimics all the features of a regular painting: the rhythm, chiaroscuro and so on. And when he hammers nails not into a plane, but into – for example, a chair or a television – we get an absurd object in a Dadaist or surrealist style. In fact, it was the Dadaists and the Surrealists who legitimised this new kind of object. And now it is an independent object; losing the connection with the image plane, it exists as a separate subject for which the usual genre definitions do not apply.

One of the most famous surrealist objects is Méret Oppenheim’s Breakfast in Fur, created in 1936, and comprising a teacup, a saucer and a spoon, all covered in brown fur. Her other equally absurdist work from 1963 is called Box with Little Animals. This is a box with butterfly-shaped pasta glued to its inside walls. In Italian, this kind of pasta is called farfalle, meaning ‘butterfly’. These pieces of pasta are the small animals in the work’s title.

Even descriptions of surrealist objects are exciting. For example, Salvador Dalí’s Lobster Telephone (aka Aphrodisiac Phone): the phone is an ordinary one from a shop, but there is a lobster sculpture resting on its receiver. Dalí himself explained this work as follows: “I do not understand why, when I ask for a grilled lobster in a restaurant, I am never served a cooked telephone; I do not understand why champagne is always chilled and why on the other hand telephones, which are habitually so frightfully warm and disagreeably sticky to the touch, are not also put in silver buckets with crushed ice around them.”

Another curious object is The Gift – a clothes iron with fourteen nails on its base by the Franco-American artist Man Ray. He also made The Enigma of Isidore Ducasse which looks like a shapeless bundle of blankets, tied with a rope. The riddle of this object unravels when we learn that Isidore Ducasse, alias Lautréamont, was a 19th century writer and idol of the Surrealists and Dadaists, for whom his saying, “Beauty is the chance encounter of a sewing machine and an umbrella on an operating table,” was of great importance. Hence a sewing machine hidden inside the blanket.

A beautiful story occurred with Man Ray’s work entitled Object to be Destroyed, created in 1923. It consisted of a metronome with a small photograph of an eye attached to its swinging arm. The eye belonged to Lee Miller, a photographer, model and, at that moment, Man Ray’s lover. The metronome was accompanied by an instruction: “Cut out the eye from a photograph of one who has been loved but is seen no more. Attach the eye to the pendulum of a metronome and regulate the weight to suit the tempo desired. Keep going to the limit of endurance. With a hammer well-aimed, try to destroy the whole at a single blow.” In 1957, a group of protesting students broke into an exhibition in Paris where the Object to be Destroyed was exhibited, stole it and actually destroyed it, not with a hammer but with a gunshot. As Man Ray was still alive, he gladly made a few more copies of the work, but changed its name to Indestructible Object.

We might say that the absurd dominated the world of objects. Objects in Pop Art follow the same poetics. Naturally, consumer society is the main target of Pop Art and it comes as no surprise that it parodies or critically replicates major consumer goods. For example, the American Pop Artist Claes Oldenburg erected huge monuments to such simple things as clothespins, shuttlecocks, forks, spoons, and ice cream cones. These could be referred to as anti-monuments. In his works, spoons turn into bridges, realistic ones at that, while still remaining just spoons.

Objects similar to Western Pop Art were made in Russia as well. For instance, the Sots-Artist Alexander Kosolapov produced a series of objects, similar in concept to those by Claes Oldenburg, but not as gargantuan in scale. Kosolapov made oversize wooden portraits of common Soviet objects: door latches and meat grinders and the like. His work Bather serves as another example. It takes the form of a large, slightly open, wooden matchbox with a female bather peeking out at us from inside – a sculpture hidden in a box.

Boris Turetsky’s assemblages also deserve mention as an example of the Absurdist movement. He was one of the most interesting artists of the underground. Let’s examine the work Nude, conceived in 1974. A woman’s garments are glued onto a sheet of hardboard. Attached from the bottom upwards are shoes, stockings, gloves, panties, a garter belt, and a bra. The woman herself is not there, but the objects that symbolise her are present.

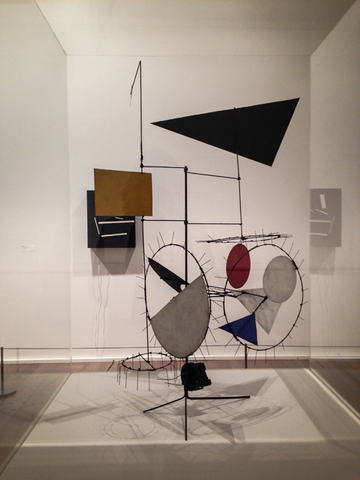

We have already covered those objects that draw on painting and sculpture. We must now speak about kinetic objects that depend on movement, of which Alexander Calder’s mobiles were the first. These mobiles are made of multi-coloured shapes, suspended from the ceiling or mounted on a wall, that move in response to the movement of air currents. These shapes usually evoke those found in nature. Calder was also close to Surrealist and Dadaist circles. The theory of relativity, the uncertainty principle and other scientific discoveries of the 20th century cast doubt on the very foundations of the physical world. This cloud of doubt fed the art of Surrealism and Dadaism, which surveyed the perturbed, irreparably unbalanced universe. There was a positive side to this chaos, however: what freedom is found in times of great uncertainty! This is why Calder opted for sculptures that move unpredictably and react to every single breath of air. These colourful mobiles dangling in the air are deceptively playful and cheerful, when they really stand for a very serious artistic statement.

Jean Tinguely came from the next generation of kinetic artists, and his mechanical sculptures correlated with these ideas. He came to design his ‘machines’ after first experimenting with assemblages, among which were the works Meta-Malevich and Meta-Kandinsky (although they were most likely inspired by Tatlin). The prefix ‘meta’ was Tinguely’s signature mark. He called his objects ‘metamatics’, ‘meta-harmonies’, and so on. They were usually fairly large objects consisting of such miscellanea as wheels, scrap metal, household objects and their remnants, light bulbs and percussion instruments. His sculptures glowed, made noises, and some, like the metamatics, could also paint; the spontaneous drawings of these 1950s ‘machines’ mocked the abstractions that were so respected at the time.

From around the late 1950s his sculptures became self-destructing – with the disintegration and breakdown of the machines now being part of the concept. Each machine demonstrated both a mechanic function and its own death, which, conceptually, is also an ironic turn. Irony aside, Tinguely’s objects worked well either as toy, or as attractions. There was a peculiar incident at Tinguely’s exhibition in Moscow: it was held during Perestroika, when Russians were not yet accustomed to new kinds of art, and so pressing the buttons and switching the machines on was strictly prohibited. Objects intended to move were displayed static, making the exhibition hall into a truly total installation.

Tinguely’s Manifesto for Statics concerned the notion of total movement. In 1962, Russian kinetic artists named their group accordingly – Dvizheniye (‘Movement’). Founded by Lev Nussberg, it was made up of many artists, among which were Francisco Infante-Arana and Vyacheslav Koleichuk, as well as physicists and biologists. Generally speaking, this movement was a flaring-up of radical Constructivism, its new stage. The 1960s were a period of strong faith in technological progress and the triumph of ‘physicists’ over ‘lyricists’, and Dvizheniye was intoxicated with the new mechanical possibilities. Their practice was constructed on a confluence of scientific knowledge and artistic methods of production. Their works have not been preserved, and only photographs and descriptions remain. The group’s kinetic sculptures incorporated light and sound – their scope similar to that of installations. The artists of the Dvizheniye group wanted to redesign the visible world, and create designs for cities and mass events. And it’s hardly their fault that this never happened.

The time has come to talk about installations. What exactly is an installation? It’s a certain environment, designed according to a specific plan and artistic concept. The degree of artist participation in its design can significantly vary – for example, artists may use already-existing sites which viewers are invited to explore from a different perspective. In any case, installation is yet another instance of play on the seemingly indiscernible fringe of art and life. Sometimes one’s focus has to be shifted in order to perceive it.

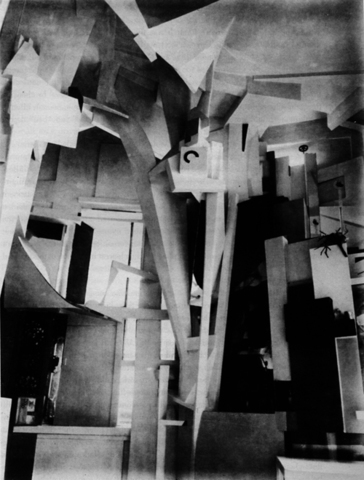

Like many other kinds of art, installation art also begins with Dadaist inventions. Its origins can be traced back to two works by the German artist Kurt Schwitters. The first was a column that he built in his own house using scavenged scrap – in fact, this was a prototype for junk art, art made from waste. Schwitters lived in a multi-storey house; the column kept growing, and when it hit the ceiling of a room, the ceiling was broken, and the column was free to grow higher into the next floor.

The column’s story continued with Merzbau, which saw the artist’s entire house in Hannover transform into a total installation. Objects took over the three-storey building and ultimately made living in the house impossible. The idea behind this work was the blending of life with art to create a synthetic whole. ‘Bau’ means structure and ‘Merz’ is a fragment of the word ‘Commerzbank’, chosen purely by chance. The installation itself had grown as if by chance, following the flow of life. Schwitters made the syllable ‘merz’ his own special meme and defined it as the “creation of links between everything in the world”.

The word ‘installation’ has recently come to be used in widespread conjunction with the word ‘total’. This term primarily refers to an artwork’s scale: the work does not take up a fracture of space, but fills it entirely – whether it be an entire room, house, or gallery. It may also indicate use of various multimedia approaches: computers, videos, or technology in general. Contemporary installations of this kind often mutate into overly ambitious spectacles.

And yet the term ‘total installation’ had been coined by Ilya Kabakov to convey a very different meaning. It was the series by Irina Nakhova entitled Komnaty (‘Rooms’), created over five years from 1983 to 1987, that Ilya Kabakov named ‘total installation’. Once a year, Irina Nakhova would completely renovate one of the rooms in her apartment: she would either get rid of the furniture or keep it, but would cover the walls in white paper, repaint them or fill them with images from fashion magazines – in short, she manufactured new space experiences from the same spatial box. The word ‘total installation’ here indicates not only the duration of the process, but also its reiteration. It also points to the existential significance of the work, as whole lives are lived in such installations.

In her later works, Irina Nakhova frequently employs modern technology: video, sound, and interactive features. In her installation Big Red, Nakhova presented a very large and very red inflatable creature. Upon being approached by a spectator, it grows in size and reaches forward; if the viewer walks away, Big Red deflates disappointedly. This is a very distinct and amusing comment on communication in general, and specifically about the relationship between the art and its viewer.

And, finally, we mustn’t leave out Ilya Kabakov’s installations. These, too, are total in the sense of their existential density: in them, the artist works with one subject of particular personal poignancy to him. His relatively early installation The Man Who Flew into Space from His Room comprises a very cluttered room displaying the tokens of meagre communal living. There is a catapult right in the middle of the room and a hole in the ceiling – the man has flown away. Let’s look at one of his later works entitled Toilet – a vanishing point of all Kabakov’s reflections on communal living. We see a typical railway station toilet, with the signs for the gents’ and the ladies’, and everything else that comes with it. However, inside the room, in addition to the ordinary toilet facilities, one finds oneself in the typical, even cosy, atmosphere of a standard Soviet apartment. When Kabakov exhibited this installation, the critic Andrei Kovalyov wrote (and he had a point) that now the Western public believes that Russians lived in toilets. That’s one way to look at it.

In fact, you can look at it in many ways, as this kind of art is open to interpretation. And besides, the 20th century brings us art that is more open to direct interaction with the viewer. In these interactive works, the artist can move outside his regular role and act as a curator, or organiser. We’ll talk about this sort of art in the next chapter.