Russian Modern

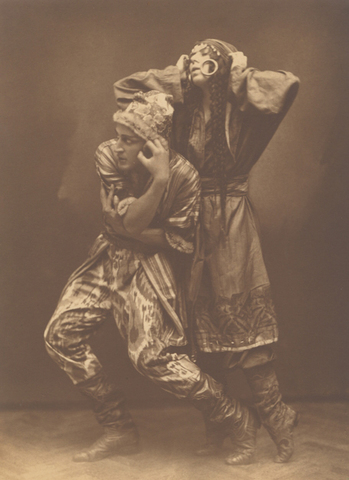

There’s an established public perception that it wasn’t until the 1910s and the Avant-Garde movement that the 20th century really began in Russian culture. It was the Avant-Garde that brought Russian art into the European world, and this was our contribution to world culture, our brand, and our everything. Very rarely do people remember those who prepared the ground for this triumphant coming out onto the international scene. At most, they mention Diaghilev and his Ballets russes that so triumphantly premiered in Paris in 1907. But the aesthetics of Diaghilev’s ballets that the Europeans raved about had been shaped by the circle of artists who made up the Mir Iskusstva (World of Art) movement. These had succeeded in recalibrating the optics of art perception, carrying out a quiet, but substantial revolution. They had built a springboard for those who came after them and who – quite naturally – treated their predecessors with disdain.

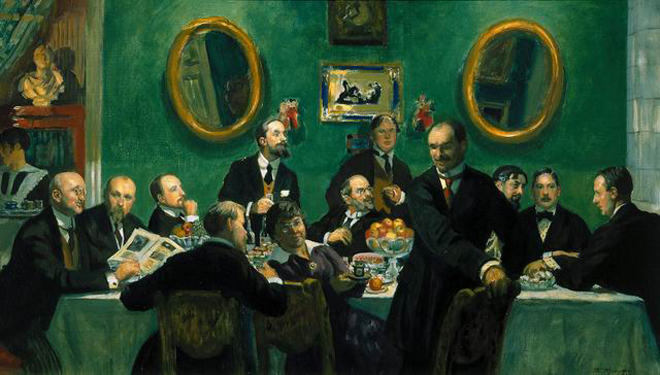

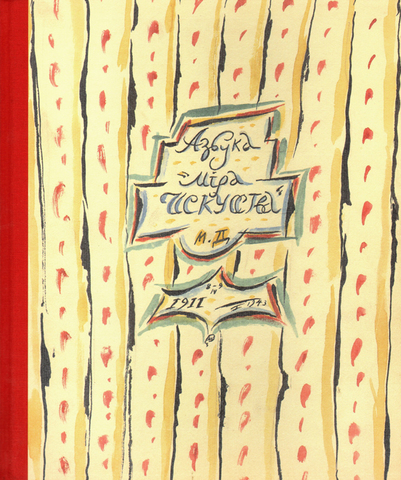

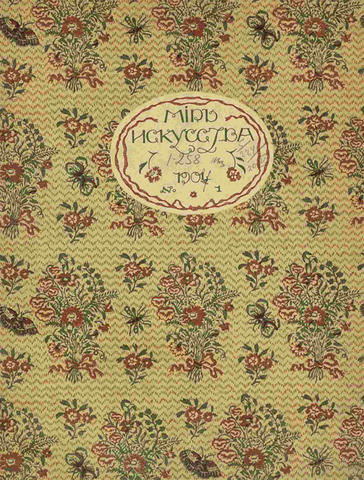

It was a very narrow circle. Just a handful of people made up the core of the World of Art movement, which began to publish an eponymous magazine in 1898. These were the artists Alexandre Benois, Konstantin Somov, Léon Bakst, Eugène Lanceray, Mstislav Dobuzhinsky, and Anna Ostroumova-Lebedeva. And, of course, the group included Sergei Diaghilev – entrepreneur, promoter, and the driving force behind the movement’s initiatives. There were also men of letters – the critics, headed by Dmitry Filosofov. The magazine published articles by Fyodor Sologub, Zinaida Gippius, Andrei Bely and other Russian Symbolist poets – but then the writers had a falling out with the artists, and defected to the Novy Put’ (New Way) magazine. Within this tight circle, the majority of members were connected through kinship or school friendships. World of Art itself was born out of an even more intimate group called the Neva Pickwick Club in honour of Dickens’ novel. The friends would gather to lecture each other on art history. Alexandre Benois was, most likely, the group’s Mr Pickwick – and even his appearance, round and spacious, suited that role.

Late in life, Benois, then an émigré in France, published two volumes of his memoirs. He recalled his childhood and the hobbies of that time: toy collections, cardboard city models, and his love for optical toys such as the magic lantern. He said that all of these things determined his stance towards art as magic: art had to be different from life, because life itself doesn’t make people happy, being monotonous and hard on the eye.

On the one hand, the members of this movement wanted to leave behind real life in favour of some more notional kind of world. Where to find such worlds? In the past, of course. And how do we know anything about the past? We see it in art, and it is precisely these images that inspire us. The World of Art members were interested in art much more than they were interested in life. They saw the art of the past as capable of giving birth to another, new craft. They didn’t care for history as it was, they only wanted its images – fabricated, fleeting, and accidental. ‘Retrospective dreams’, ‘courtly festivities’, ‘royal hunts’ – no grand ideas, just the acute experience of a bygone atmosphere. Today, we would call it escapism.

On the other hand, this unattractive, mundane, modern world could be transformed and repurposed, made to look different. It could be saved by beauty – by making a sweeping change in interior design, books, buildings, and clothing, so that everyday life would become different, not just art. It was a rather paradoxical combination of escapism with a passion for reform and design. Amazingly, these people did actually manage to achieve their grandiose objective and change the tastes of a whole epoch. Prior to the World of Art, the Russian public was used to narrative paintings with a clear plot, whether by the Peredvizhniki (the Wanderers) or from more academic artists. But World of Art and its activities prepared the public to readily embrace the Russian Avant-Garde.

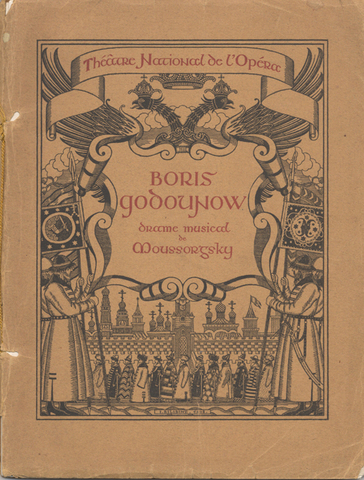

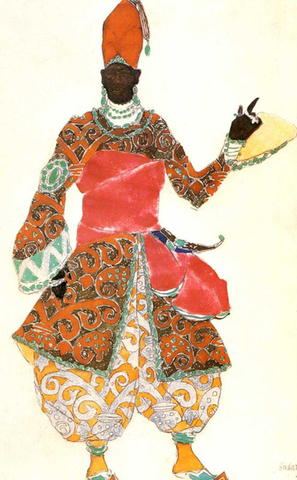

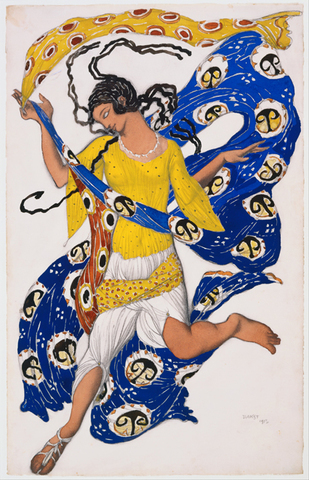

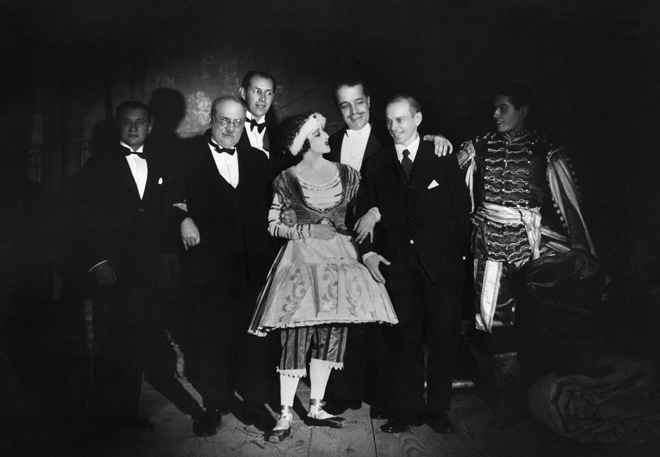

Let’s turn now to those areas in which the World of Art members proved particularly successful. They completely changed theatrical design, for instance, especially in musical theatre. Before they came along, artists had no place in the Russian theatre. All stage props were taken ‘from the selection’, that is, from a limited range of standard ready-made stage sets. Certain backdrops were used for any play about mediaeval times, and others – for anything set in Ancient Egypt. The World of Art members, however, worked with each performance individually, with the precision and attention to detail worthy of a restoration artist. Thanks to them, theatrical artists became the equals of stage directors – with Benois even writing librettos himself.

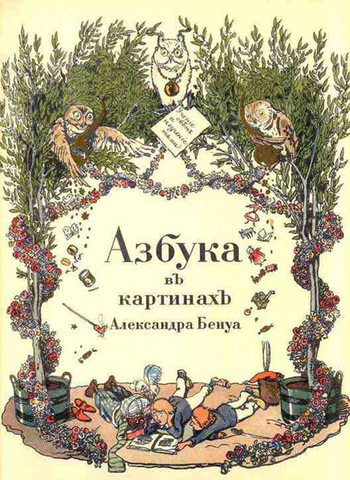

They also completely changed the appearance of illustrated books. Formerly, illustrations in such books would be commissioned from different artists, and might thus produce stylistic clashes in any given book. The artists from the World of Art group put forward the idea of a book as a single entity, in which images have to be compatible with the text, and where all of the vignettes and headpieces should be executed in a single common style. They viewed books as visual performances for which artists were the directors and set designers. This idea of a synthesis between art and text was first brought to life in their own World of Art magazine, which we’ll speak about shortly.

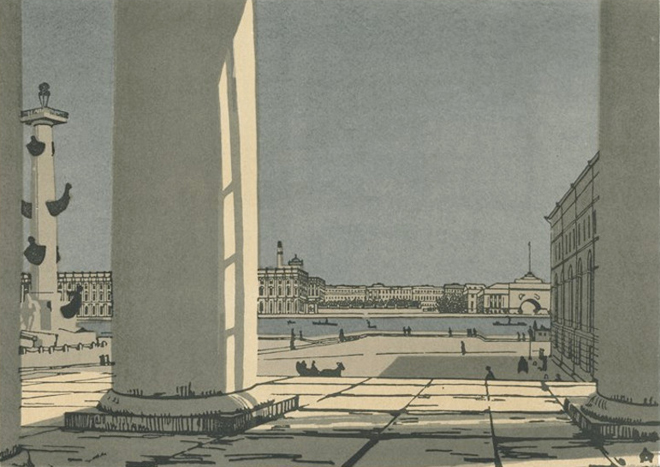

It would be hard to enumerate everything done by these artists – there were too many ‘micro-revolutions’. But one thing definitely deserves mention: the way we perceive Saint Petersburg today owes everything to the World of Art members. Back in 1903, Russia celebrated the city’s bicentenary, and the style of the celebrations was in many ways presaged by the artists’ efforts to change the capital’s image. Before the World of Art, Saint Petersburg hadn’t been considered a beautiful city at all. It had two public images, both very unpleasant. On the one hand, it was a formal and bureaucratic city, as opposed to the lively, turbulent, diverse, and free-wheeling Moscow. On the other hand, it was the city of Dostoevsky: a place of dark courtyards resembling deep shafts, wrapped in constant twilight. All of this was transformed by the efforts of World of Art members – partly Mstislav Dobuzhinsky, but mainly thanks to Anna Ostroumova-Lebedeva. There’s a well-known saying that Russian nature was conjured up by Savrasov, and later by Levitan: before them, nobody had cared to think of it as visual material at all. And so, drawing a similar parallel, we could say that Saint Petersburg was dreamt up by Ostroumova-Lebedeva.

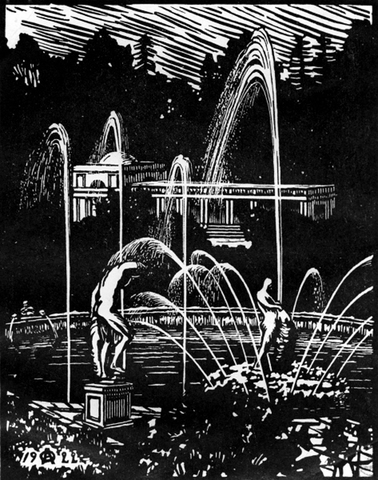

And, true to form, she did this in engravings. In addition to everything else, the members of this art group revived graphics as a separate kind of art in itself. In Russia, the graphic arts had always filled a supplementary role: being used as etudes and sketches for paintings, but never considered worthy of their own separate display. The graphics used in magazines were often no more than reproductions of paintings. The World of Art members revived the unique graphic arts of original drawings, but went further, popularising printed graphics as well. Ostroumova-Lebedeva, in particular, practised coloured engravings on wood, basing her work on Japanese engravings that were still unfamiliar in Russia.

The artists who made up the core of the movement were all very different, of course, but there was a certain common poetic style that united them. The essence of this style can be found in the works of Alexandre Benois and Konstantin Somov.

Benois was in love with the 17th century France of Louis XIV and with the Russia of Catherine the Great and Paul the First. His Versailles Series and the Last Promenades of Louis XIV cycle depict a fragile, fabricated world of marionettes. The pictures weren’t executed in oil on canvas, they were watercolours on paper – and as a result had none of the solidity associated with oil paints, with no absoluteness, no obligations. These weren’t historical paintings, these were historical pictures. What is a historical painting in the Realism tradition of the 19th century, exemplified by someone like Vasily Surikov? It’s a certain idea about the meaning of history, compressed into a single episode. But if a World of Art member had sat down to paint Surikov’s famous work Morning of the Execution, it’s quite possible that he wouldn’t have focused on the execution or Peter the Great at all, concentrating instead on a passing magpie. Benois’ historical pictures are always about accidentally snatched fragments that don’t show any main events, but give off instead a faint whiff of history. The same acuteness and happenstance of angles can be found in Valentin Serov’s Royal Hunts and his watercolour Peter I. Here, the grotesque figures of the huge Peter and the hunched-up courtiers against the backdrop of notional ‘desolate waves’ combine irony with a sense of historical scope. Not for nothing was Serov the only Moscow artist to sit on the board of this art group; he was on quite the same wavelength as the others.

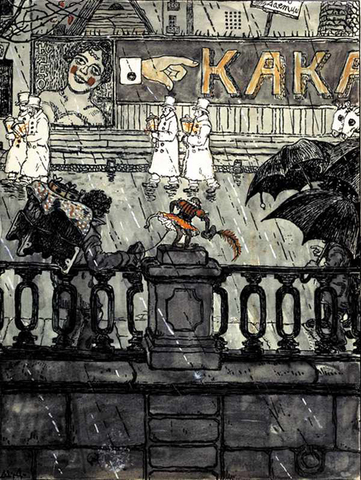

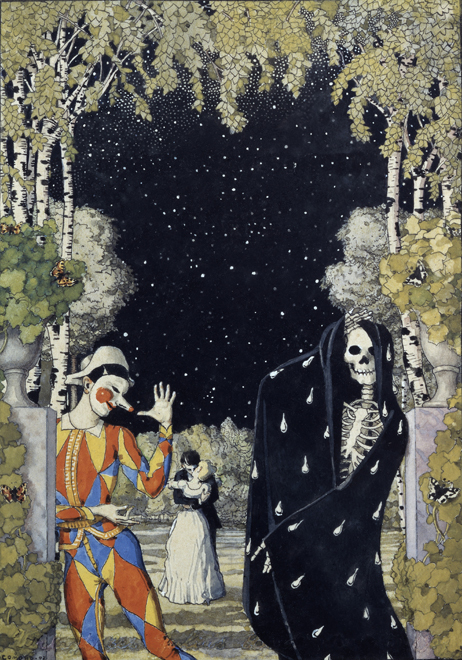

Unlike Benois, who was inspired by specific historical periods, Somov replicated a certain notional fête galante – whose exact dating to the 17th or 18th century was immaterial. Marquises with cavaliers, harlequins and other characters of the Italian commedia dell’arte, masquerades, sleeping or daydreaming ‘damsels of times gone by’. These works were more about mockery than a melancholy for something now lost. Melancholy was present, but it pined for other things, unattainable because they belong not to life, but to art. A constant theme in his work was of things which flare up and are then extinguished – rainbows, fireworks, bonfires. The end of a celebration, always brief, like a spark.

Contemporaries regarded the Lady in Blue as Somov’s principal work – a portrait of the artist Yelizaveta Martynova, painted shortly before her death from tuberculosis. A sad girl wearing a moire dress of the 1840s stands with a book, and behind her, far away, is a vision from the book: a cavalier and a lady flirt on a bench, as a flaneur with a cane, resembling the artist himself, passes by. It’s a painting about the futility of romantic impulses in a prosaic world, and that was exactly what its first viewers saw in it.

But there were those among the World of Art members who had no use for nostalgia. One of them was Léon Bakst, who had most fulfilled himself as the art director of Diaghilev’s Ballets russes. Paris’s top fashion designers – Paquin, Poiret, Wort, and others – would all come to use his ballet costumes as the starting point for their own designs. There was also Dobuzhinsky, who, unlike his associates, forsook the musical theatre for the dramatic, joining Stanislavsky at the Moscow Art Theatre. He oversaw the production of several plays there, two of which particularly stand out. One of them, based on Turgenev’s A Month in the Country, followed the World of Art aesthetics, and was a trove of antiques. The other, Nikolai Stavrogin, based on Dostoyevsky’s work, was a sombre piece, and quite symbolist in nature. On the whole, Dobuzhinsky wasn’t averse to Symbolism, and his later works even veered into abstract art.

Dobuzhinsky’s watercolours and Ostroumova’s block prints of Saint Petersburg views were distributed in the form of postcards published by the charitable organisation “The Commune of Saint Eugenia.” Producing postcards was another important feature of the World of Art program. Postcards were a popular form of art, with mass circulation, often used as souvenirs. They fit in well with the artists’ principal idea that there should be no distance between popular and high art.

All in all, the World of Art painters were a completely new breed of artists. First of all, they were amateurs. Some of them had dropped out of the Academy of Arts, others had attended a few classes in private Paris studios. But almost all had fled something due to their boredom with standardised art and standardised education.

Secondly, all of them were intellectuals, something totally uncharacteristic of previous generations of Russian artists. They were well-read, they spoke various languages, they were cosmopolitan in their endeavours, and they were music lovers, organising contemporary music concerts at the offices of the World of Art magazine.

Thirdly, they were all quite bourgeois. Traditionally, the bourgeois way of life had been contrasted with the romantic image of the artist, but the members of this group insisted on it. And yet they were all of very different social backgrounds. Benois came from a noble family of French origins, Somov was the son of the principal Hermitage curator, that is, from a professorial intelligentsia family, while Bakst was a Jew from Grodno, but this had no adverse effect on their companionship: they spoke the same language, and they had the same manners.

And there was a very important nuance in those manners. The entire second half of the 19th century in Russian art, termed the Peredvizhnik period, was based on the pathos of duty. The artist always had a duty – to the people, to society, to culture – to whomever and whatever. The World of Art members were the first to claim that the artist owes nothing to anyone. The keynote of their lives and art was an ode to caprice and whimsy, to carefree artistic gestures. From there it was but a stone’s throw to the unrestricted gestures of the Avant-Garde, but the origins of that future freedom can be found here.

The members of the World of Art movement had a favourite word, skurilnost, derived from the French scurrile, meaning ‘salaciousness’. What kinds of things were scurrile for the artists? These were devoid of any qualities of importance or solidity. Something comical, perhaps, something lonely, or something vulnerable. It could be a toy or some sort of petit-bourgeois rug. This cult of the lack of commitment was another important nuance of their collective programme.

As the artist Igor Grabar wrote to Alexandre Benois, “You are too enamoured of the past to value anything contemporary,” – and that was the absolute truth. The artists were in love with an imaginary past, a dream, a certain image of beauty that can be observed from the audience through inverted binoculars. There was admiration in this, and irony too. There was also bitterness and remorse.

And they were people – very private people with a certain system of values – who wanted to reorient Russian culture towards the West, and to transform the entrenched tastes of society. In order to do that, they published a magazine, styled after the European magazines that promoted the Art Nouveau. There’s no doubt that the aesthetics of the World of Art were another version of the Art Nouveau.

Each country had its own name for this style: modernist, Secessionsstil, liberti, Art Nouveau, or the Jugendstil. Simply put, the ‘new style’. The word ‘style’ itself is important, because it signifies preoccupation with form. In each country, the modernist style existed in its own form, but some things were universal – the forms were taken from humanity’s common cultural background, from the collective memory. This universality served as a foundation for the individual, as the past gave birth to the present. Before the World of Art movement, there had been no preoccupation with form in Russian art, only with content, and there had definitely been no style. And the same was true elsewhere.

Art Nouveau is an artificial style, which could not have emerged on its own. To put it bluntly, it was the product of the Industrial Revolution. The automated production of identical objects and identical ways of life provoked a psychological and aesthetic rejection. The principal idea of Art Nouveau was manual labour. It all started in England with the Arts and Crafts Movement led by the novelist, publisher and artist William Morris. Later, branches of the movement began to appear in other countries too. They sought to achieve two goals: to produce individually-made things that were beautiful, and to unite the craftsmen who produced those things. In its earliest incarnation Art Nouveau was closely connected with socialist ideas.

As a result, the early European Art Nouveau movement was two-directional. On the one hand was the archaic, restorative vector: everyone is building huge factories, but we are going back, to craftsmanship and the medieval guilds. But on the other hand, there was a futuristic vector too, because everything was done in the name of a utopian future. In the long run, the whole world would be saved by beauty and transformed into an unadulterated City of the Sun.

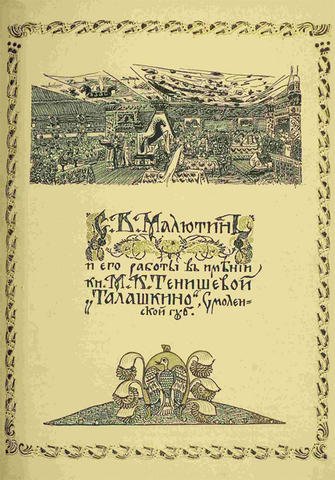

But we must go back to the World of Art movement. To publish a magazine, you need sponsors. But who would finance the artists? Surprisingly enough, a significant sum was donated by Nicholas II on the request of Valentin Serov, who had painted the Emperor’s portrait. But there were two permanent sponsors as well. The entrepreneur and art patron Savva Mamontov, although he would go bankrupt by 1899, and Princess Maria Tenisheva, who subsidised the publication to the very end. Both Mamontov and Tenisheva initiated a Russian programme in the likeness of the English Arts and Crafts Movement. They used their estates – at Abramtsevo and Talashkino respectively – to create artists’ workshops. Mikhail Vrubel, for example, famously painted balalaikas and fireplaces at Mamontov’s estate. This was no sign of disrespect for the artist, but quite the opposite. It should come as little surprise that this duo should support Benois and Diaghilev.

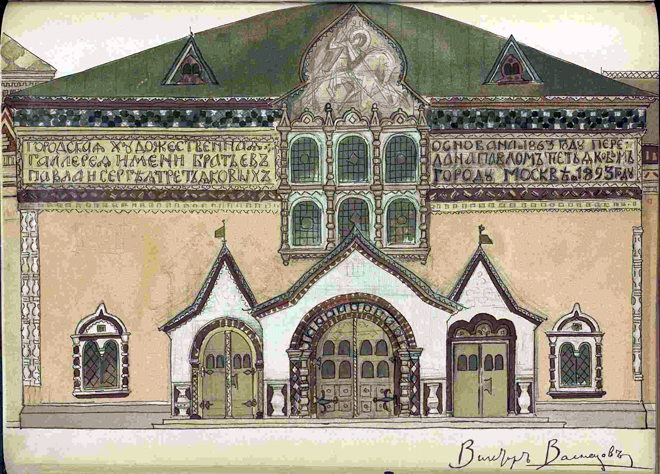

The magazine had a six-year history, from 1898 to 1904. Among its subsidiaries were the “Modern Art” showroom, which sold furniture, porcelain, and so on; the “Evenings of Contemporary Music” gatherings; and another magazine – Russia’s Artistic Treasures, also edited by Benois. Exhibitions of Russian and foreign art were held – five altogether, with another three organised by Diaghilev even before the magazine got off the ground. Diaghilev was the driving force behind all their initiatives, a man of irrepressible energy and outstanding talent for organisation. One of his most sensational projects was the historical exhibition of Russian portraits which he used to introduce the Russian public to the national art of the 18th and early 19th centuries. Diaghilev curated the exhibition himself, travelling around noble estates in search of paintings and practically beguiling the owners in order to have them part with the portraits. In 1907, he organised a series of Russian concerts at Paris’ Grand Opera, and that gave birth to the famous Ballets russes – a private theatrical enterprise that lasted for over 20 years.

Diaghilev moved abroad, and oversight of the movement’s activities fell to Alexandre Benois, who was more an ideologist than an organiser. The World of Art went into decline, but the possibility of this rapid demise was actually embedded in the premises, on which the movement operated. Its members, who so valued their intimate circle and their friendships, were extremely tolerant and embracing when it came to the politics of art. They were ready to collaborate with anyone and to draw others into their project. Everyone who possessed a spark of life, even if its precise qualities were alien to the founding members themselves, was welcome. The magazine’s first issue contained many reproductions of Viktor Vasnetsov’s paintings, even though the publishers were no fans of his art, and World of Art as a whole was opposed to the ideas of the Peredvizhniki. They were convinced that Ilya Repin and his style were out-dated, but nonetheless published reproductions of his paintings, admitting their importance. And this was happening at the time of the first manifesto wars, as artists strove to demarcate their territories, and were ready to fight earnestly for their views on life and creativity. Under such conditions, the idea of universal unification in the name of an aesthetic utopia was, no doubt, very vulnerable.

For the sake of the unification ideal, members of the World of Art made a grand gesture in 1904 of abandoning their brand and joining the Moscow-based Union of Russian Artists. This organisation was full of landscape artists working in the vein of Savrasov and Levitan, and its members were enamoured with Impressionism, which was alien to the artists from Saint Petersburg – ultimately rendering unification impossible. In 1910, World of Art restored its own name, but its members did not forego the idea of collaborations, and their exhibitions began to include the Symbolists from the “Blue Rose,” the rebels from the “Jack of Diamonds” group, and pretty much anyone else – even up to and including Malevich.

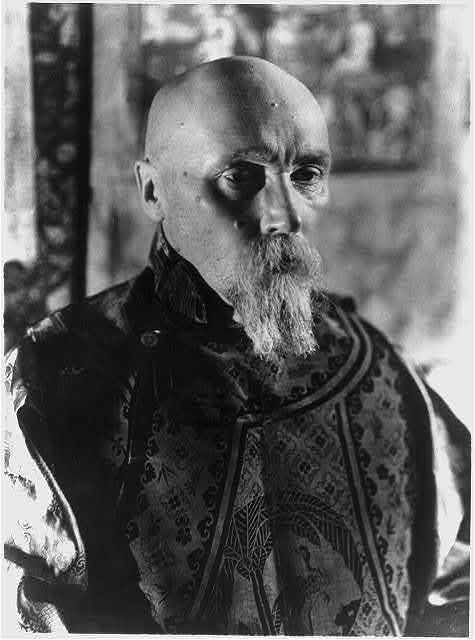

Benois refrained from exercising his authority, which is why, in 1910, the leadership of the World of Art was passed on to Nicholas Roerich, whose human qualities and artistic visions were in many ways antagonistic to those of the original founders of the movement. In 1921, the movement was taken over by Ilya Mashkov, the most shameless member of the “Jacks of Diamonds” Avant-Garde art group, who simply usurped the brand. But this was really a posthumous existence, though the World of Art wasn’t formally disbanded until 1924. By that time, none of its founders remained in Russia except for Benois (who emigrated soon afterwards), Lanceray, and Ostroumova-Lebedeva.

It should be pointed out that the ideologists and creators of the World of Art partially recognised the evanescence of their undertaking. They foresaw the advent of another way of life and the appearance of other people, who would later force them out of the cultural scene. This feeling was clearly articulated in Diaghilev’s speech of 1905, at the opening of the portrait exhibition. And his prophetic words are worth recalling in full:

“Don’t you feel that the long gallery of portraits of people great and small with whom I have tried to fill the magnificent halls of the Tauride Palace is nothing more than a grandiose and overwhelming inventory of a brilliant but regrettably dead period in our history? I have earned the right to say this loud and clear, for as summer was breathing its last, I ended my long journey across the length and breadth of infinite Russia. And it was indeed after those acquisitive trips that I became especially sure the time of reckoning had come. I saw that not only in those brilliant portraits of our ancestors, so obviously distant from us, but especially in the eyes of their descendants, who were approaching the end of their time. The end was here, in front of me. Remote, boarded-up family estates, palaces frightening in their dead grandeur, weirdly inhabited by dear, mediocre people no longer able to bear the weight of past splendours. It wasn’t just men and women ending their lives here, but a whole way of life. And that was when I became quite sure that we are living in a terrifying era of upheaval; we must give up our lives for the resurgence of a new culture, which will take away from us the remnants of our tired wisdom. This is what history teaches us, and aesthetics confirms. And now, immersed in the history of painted effigies, and thus made immune to accusations of extreme artistic radicalism, I can state frankly and firmly that such conviction as I have cannot be wrong: we are witnessing the greatest historic hour of reckoning, where things are coming to an end in the name of a new, unknown culture, one which we will create but which will in time also sweep us away. And therefore, without fear or doubt, I raise my glass to the ruined halls of those beautiful palaces, and in equal measure to the new commandments of the new aesthetic!”