Conceptualism and Sots Art

Here’s Stalin, in generalissimo uniform and striped trousers, enjoying a drink with a scantily clad Marilyn Monroe. A huge calico ball is floating down the river Klyazma, with lots of inflated balloons and one ringing electric bell inside it. And here’s a public toilet – but with Soviet apartments behind the doors to the Ladies’ and the Gents’. All of this is Russian Conceptualism.

It wouldn’t be too much of an exaggeration to say that almost all contemporary art descends from Duchamp’s ready-mades. From his work Fountain, to be more specific – an ordinary urinal exhibited as a work of art. This 1917 object can also be considered the first piece of Conceptualism, a movement that had not yet been formalised as a phenomenon and had not yet been given a name. This would happen much later, in the 1960s.

American artist Joseph Kosuth would become the real father of the already articulated Conceptualism. In 1965, he created his major piece One and Three Chairs. This is an installation comprising a chair, a photo of the chair and a dictionary entry with the definition of the word ‘chair’. The chair is presented as one in three entities. Moreover, every time the work is exhibited, only the dictionary definition remains unchanged – the chair and its photograph are different each time. Kosuth has reprised this piece with several other objects – a shovel, a mirror, a hammer, a saw, and so on.

At the age of 24, Kosuth wrote an essay titled Art after Philosophy, in which he claimed that traditional art, and modernist art in particular, was coming to an end, and that it was now time to study the nature of art rather than to create it. The main thesis of the piece is “Art is the power of an idea, not a material.” Any object can become a conceptual object, as well as any documentation on the object: a text about the exhibit itself replaces the exhibit. A conceptual object can’t be sold and is excluded from the commercial field, because there is in fact nothing to sell – there is no craftsmanship in its execution, no aesthetics, and no novelty. This is art dedicated to how art is organised: that is the tautology.

Conceptualism was born out of disappointment in the old picture of the world broadcast by traditional art. What is traditional art? It is a kind of art more or less based on the principle of mimesis, the imitation of something that exists in reality. The artist depicts something that can be compared with its prototype outside the picture – a painted chair and a real chair. We can judge the skill of the artist based on this correlation; we can judge it in different ways: one person might see great skill in the exact replication of the natural world, while others, on the contrary, might see this in the expressiveness of conventional artistic language. This measure of evaluation does exist, it is objectively possible. Of course, modern art tries to overcome mimesis, and it succeeds – abstract art doesn’t directly correlate to anything outside itself, for example. But this is the point where artistic ambitions take off: a certain gesture of primacy, the manifestation of one’s self. But who gave the artist the right to manifest their Self? This is one of the main issues for Conceptualists.

For Conceptualists, the very necessity of the presence of the author in a piece is compromised. Personal presence is a matter of having a distinct style, a signature, or a single word uttered in the first person, all of which is interpreted as a totally unfounded claim to power. To the power that is manifested in the statement: “I am the author, this is my space, I created something that didn’t exist before.” This unfounded claim to power is denied and exposed to ironic disparagement and playful deconstruction. Since the initial thesis is that everything has already been said and created, the task is now to deal with the individual pieces that reality has broken into, understanding the possibilities of art, its boundaries, and its context.

There are many words in Conceptualism – this is, after all, a form of art that speaks about itself, and with no less articulation than a paper by an art historian. In literature, Conceptualists strive to free language from ideology. They work with hackneyed phrases and with linguistic clichés alienated from the human being – for examples of which we might recall Vladimir Sorokin’s prose, Lev Rubinstein’s poetry on index cards, or Prigov’s poems written in the person of a character by the name of Dmitry Alexandrovich Prigov. As for the visual arts, the central issue of Conceptualism is that of words and images.

On the one hand, here the image of an artist or a poet loses its usual romantic connotations. On the other, Boris Groys writes of “romantic Moscow conceptualism” in his 1979 article. Let’s move on to the Soviet Union of the 1960s and ‘70s to understand this contradiction, and at the same time identify some key differences between Russian and Western Conceptualism.

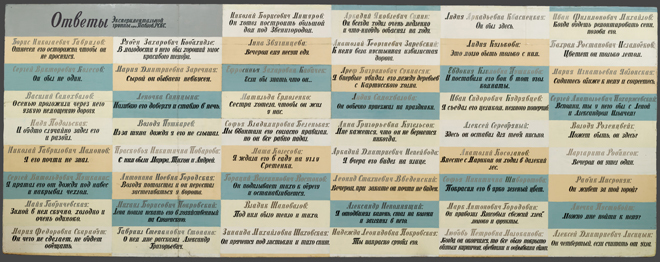

One of the first works of Russian conceptualism is Answers of the Experimental Group by Ilya Kabakov. This looks like a picture (rectangular, hanging on a wall) but instead of an image there are scraps of mundane texts with signatures that form an absurd polyphonic unity. Kabakov created other pieces in the form of stands – including the most famous example with the fly. A dirty surface, a barely visible fly, and various remarks about it. “Whose fly is this? This is Olga Leshko’s fly.” The poor fly, presented as an exhibit, is enclosed in people’s words and can’t exist outside of them, without belonging to someone – because there is nothing but language. And this Soviet language of slogans, figures, reports and schedules, road signs and official documents invades the life of the individual in an aggressive manner.

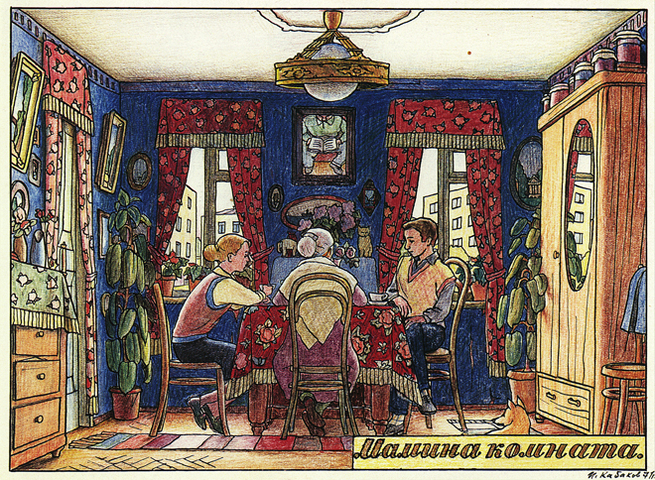

In the 1980s, Kabakov once again picked up the leitmotif of the fly with an installation entitled The Life of a Fly. In this, representatives of various different sciences argue about the fly and their speech is commented on. But the artist’s main theme shines forth most prominently in his earlier piece about the fly – it is the topic of Soviet communal living, the forced community of people. This is covered in many of his works, as for example in his 1989 installation Communal Kitchen. Western Conceptualism had no such topic – it simply had nowhere to grow from. On the one hand, the question of the fly’s ownership is poetics of Dadaist absurdity. On the other, the issue of a subject’s ownership is a legitimate and vital question for the world of a communal flat.

The kommunalka or ‘communal flat’ was the essence of a Soviet person’s world, a space which paradoxically combined the collective and the most sacred. Kabakov said: “The kommunalka is a good metaphor for Soviet life, because it is impossible to live there, but there’s no other way to live either, as it is virtually impossible to leave a communal flat.” So he nails the simple objects of Soviet life, like a grater and a mug, onto bare painted panels, exhibiting them just like the fly. He draws bunny rabbits with carrots, combining them with obscene texts written in the exemplary neat letters of a child. He creates installations out of the notes and phrases that the residents of a communal flat leave for each other. A schedule for taking out the trash written for six years in advance, from 1979 to 1984, becomes the topic’s climax.

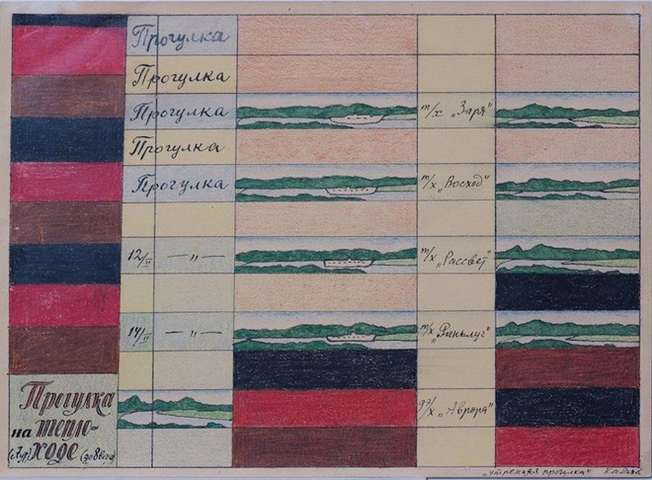

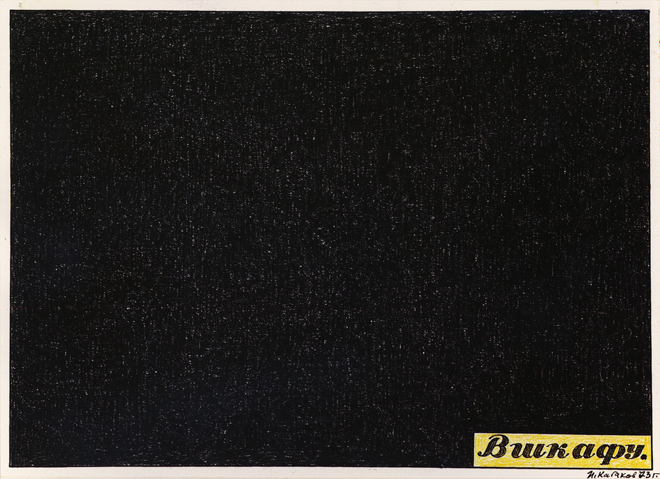

In the early 1970s, Kabakov’s first albums come out – Vshkafusidyashchy Primakov (Primakov Sitting-in-a-Closet), Poletevshiy Komarov (Komarov Who Flew), and so on: they are shown to those who come to his studio. Each album represents the story of a Soviet eccentric, usually living in a communal flat. These are strange lonely characters, often artists, who try to somehow protect their lives from the dangerous outside world. Primakov refuses to leave the closet and sees the world through its doors, while the decorator Malygin is afraid to go into the middle of a room and hides in its corners. The story almost always ends the same way – accessing the irrational: the hero disappears, dissolving into the mystical whiteness of the album sheets. Kabakov would then open all the albums in an exhibition space, making an installation out of them, with each character and their story given a compartment in a communal residence. One from which they would be able to fly off once more into whiteness and emptiness. The Man Who Flew into Space from His Apartment is an installation that was made in the 1980s; it shows the remains of a catapult in a room, and a gaping hole in the ceiling.

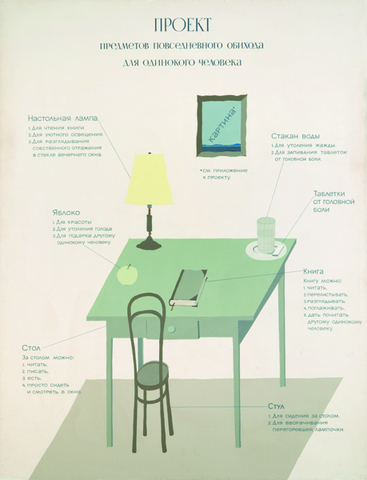

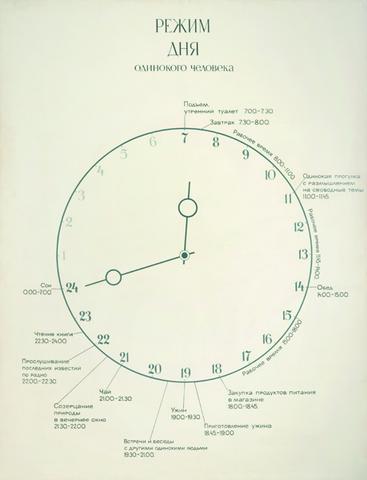

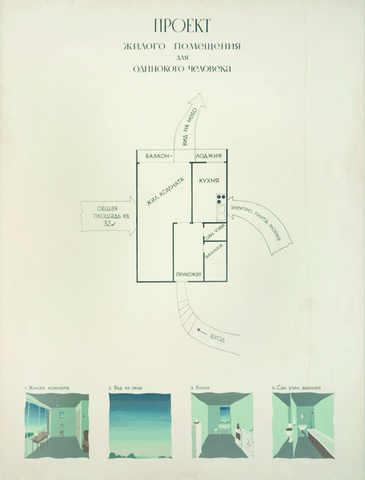

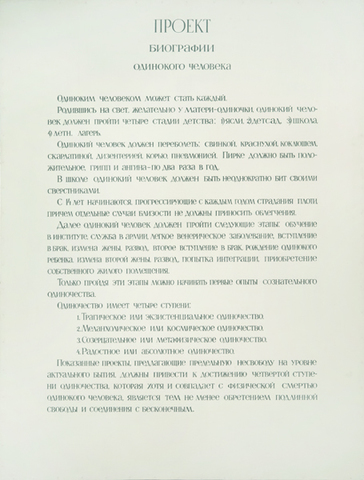

The subject of whiteness, emptiness, and radiance informs the metaphysical dimension of Moscow Conceptualism. Though an important component of Soviet Conceptualism, this subject never came up among Western Conceptualists. Viktor Pivovarov’s albums reflect this too. The texts accompanying Pivovarov’s drawings are written in the language and handwriting of impersonal safety notices, similar to Kabakov’s. For example, his ‘rules of life’ found in the album Projects for a Lonely Person resemble the smoke or radiation hazard notices of Soviet signage. The same theme is developed in the album Sakralizatory (or ‘Sacralisers’). Since every isolated person’s life goes by in an alien outside environment, one needs means with which to protect oneself from it. Pivovarov therefore suggests using ‘sacralisers’, a term he applies to everyday objects that are tied to the body. A coat hanger, for example, or a roll of toilet paper on one’s nose.

The topic of emptiness was an important one for Andrei Monastyrsky, the founder of the group Collective Actions and one of the most important figures of Moscow Conceptualism. The group’s Trips out of Town, volumes of information on the group’s performances, also figure among the most important things that happened in this circle. The Conceptualist term ‘empty action’ is connected with actions where nothing happens and the time spent waiting for something to happen is itself filled with meaning. The actions are completely absurdist, but they are absurd with a smack of Taoism or Zen Buddhism – something akin to the sound of one hand clapping.

Take the action Appearance. An invited audience appears on the edge of Izmailovskoye Field. On the other side, across the field, two figures are moving towards the audience; on approaching, they hand out pieces of paper confirming the holder’s presence at this event on a certain date. That’s the minimalism of it. The members of the audience are also the participants, and may be unaware that the walk out of the woods and across the field was the action itself and nothing more. The artistic work consists of pure time – the journey to the meeting place – as well as documentation: the piece of paper, and photography. According to Andrei Monastyrsky, the field was the stage for minimal actions, the purpose of which was to understand the linguistic categories of near, far, long, and fast.

Or consider the two acts entitled Lozung (‘Slogan’) of 1977 and 1978. People come into a forest and see a banner with a text in red and white stretched between the trees, saying “I don’t complain and I like it all, despite the fact that I have never been here before and I don’t know anything about this place”. A year later at the same place there is a banner with a different text that refers to the first one: “It’s strange why I lied to myself that I had never been here before and didn’t know anything about this place. In fact, it’s the same here as everywhere else, only you feel it more acutely and don’t understand it any more deeply.”

The most radical version of working with time was the ‘Tot-Art’ of Natalia Abalakova and Anatoly Zhigalov, two other pioneers of Moscow Conceptualism. ‘Tot-Art’ stands for ‘Total Art’; back in the mid-1960s the artists announced their lives to be art, documenting and conceptualising the events which made them up. Accordingly, their main work at a certain point in time was the birth of their daughter Eve.

Russian Conceptualism is often referred to as Moscow Conceptualism, and it really is tied to Moscow. Moreover, the members of the movement were always protective of its borders and personal composition. But inside the circle there were a variety of versions and strategies, and Conceptualism was far from homogeneous.

Ivan Chuikov, for example, explored the scope of traditional painting. His series Windows involved painting with elements of assemblage. Chuikov took closed window frames, covered the glass with white paint, and then painted an outside landscape on top of the white. So the picture is not a ‘window to the world’, but the screen onto which something is projected: the images might even spill out onto the wooden frame or appear in distorted perspective.

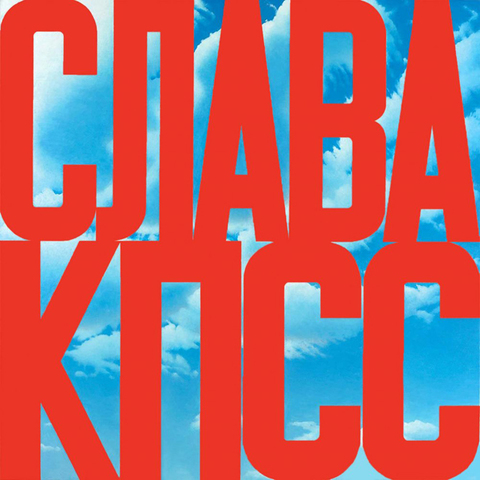

Erik Bulatov also worked with the concept of limits of pictorial space. Let’s take his early painting, Skier. A skier in a sports suit is retreating deep into the picture, but the viewer is unable to follow him: a red grid, painted over the entire surface, reminds us that the picture is only a plane, and if there is some kind of metaphysical reality behind it, access for the viewer is denied. Then there’s Krasikov Street: Muscovites are walking in the street, and a poster Lenin from a street banner is moving towards them, but they are not meant to meet. Or there’s the painting named Horizon, in which the line of the horizon turns out to be a medal ribbon or a red carpet; the official narrative is invading nature. It barges in through the accompanying text as well; in the painting Glory to the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, the titular phrase covers the sky.

Erik Bulatov is often considered to be an artist of the Sots Art movement because he uses Soviet ideological clichés and quotations. He denies it; all ‘real conceptualists’ dislike Sots artists for their mockery and don’t want to mix with them. But at the heart of Sots Art is the same conceptualist deconstruction of the claims of the authorities – except the authorities are understood here more specifically and narrowly as referring to the Soviet regime. Its language, its rituals, its art – all are deconstructed through playful parody.

Its name suggests that Sots Art is a Sovietised version of Pop Art. On the one hand, Pop Art in American culture was a reaction to the self-centredness of such abstractionists as Jackson Pollock, who poured paint onto the canvas as if he were pouring out his unique soul. On the other hand, Pop Art was a reaction to images that had become painfully familiar – in the American case, the clichés in advertising. There was no over-advertising problem in the Soviet Union, but ideological clichés were tiresomely ubiquitous.

Sots Art was invented by the artists Vitaly Komar and Alexander Melamid. They came up with the new style while they were making murals at a children’s summer camp for money – painting Lenin and heroes of war and labour, workers and collective farmers. Here’s a quote:

“So, we were drinking and thinking what bastards we were to get paid for doing this stuff. And at some point a drunken conversation started; ‘What if there is somebody out there [...], who paints such things with sincerity? And for him it’s a heartfelt cry. What does he paint? Perhaps his own family in the style of Soviet heroes.’”

And so it began: Komar and Melamid paint portraits of their relatives in the same style in which they decorated the interiors of the summer camp. They make their self-portraits in the style of the mosaics in the Moscow Metro, and around their profiles there’s a caption commemorating the heroes: “Famous artists of the early 1970s. Moscow”. They paint traditional Soviet slogans on a red background with official-style lettering. “Glory to labour!”, “Forward to the victory of communism!” But each phrase is also signed by the author: V. Komar, A. Melamid. They make a cubist portrait of the dog Laika. Finally, now in exile, they would parody salon paintings in the Socialist Realist style. They might, for example, paint a picture showing Comrade Stalin, sitting up at night with a lantern by marble columns, being visited by a half-naked muse. They would name this painting The Origin of Socialist Realism.

They also staged acts and performances. One of these was called ‘Pravda’ Cutlets - Komar and Melamid made minced meat from the main Soviet newspaper. In exile, they organised a performance Purchase of Souls, in the course of which even Andy Warhol sold them his soul on receipt, estimating its worth at zero dollars. This receipt was transferred to the Soviet Union for resale of Warhol’s soul at auction; this was another performance. The soul was to be purchased by a frontman and then to be returned to Komar and Melamid. However, Mikhail Roshal, an artist from the group ‘Gnezdo’ and a trusted friend of Komar and Melamid, failed to keep track of the bidding, and Warhol’s soul went to the artist Alyona Kirtsova - and is still in Russia.

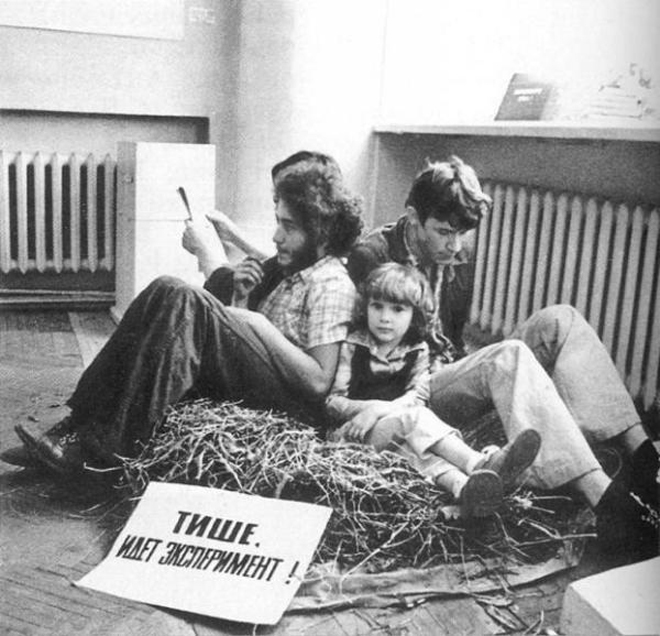

As for the group Gnezdo (meaning ‘Nest’), they present a good example of how illusory the boundary was between Conceptualism and Sots Art. Mikhail Roshal, Victor Skersis and Gennady Donskoy became famous after the performance they staged at a VDNKh exhibition in 1975 – one of the first and few legal exhibitions of underground art. They built a big nest (from which they took their name) and proceeded to hatch an egg, causing disapproval from ‘senior’ Conceptualists, who regarded this as tomfoolery. The artists of the Gnezdo group belonged formally to the Conceptualist circle, but allowed themselves some Sots Art mockery. Roshal’s portraits of Sakharov and Solzhenitsyn, made respectively out of sugar and salt in reference to the surnames of these two prominent dissidents, were confiscated during a search of his apartment. Then, in the era of Perestroika, he tried to get his work back, but to no avail – apparently, the sugar had melted and the salt had scattered during their captivity.

For Sots Artists, any sense of humour, even the most risqué, was ‘permitted’. There are some hilarious art works by Alexander Kosolapov, where the clichés of Soviet ideology and American consumer culture are mixed together: Lenin, Mickey Mouse, Stalin, Coca-Cola and so on. Some of these works made in exile would enrage religious fanatics in Russia – for example, the caviar icon or a compound image of Christ with the McDonald’s logo. The works of Leonid Sokov show the same direct and mocking clash of contexts – Stalin drinking with Marilyn Monroe, Lenin shaking hands with Giacometti’s modernist Walking Man sculpture. This art is very direct and has no second or third meanings – but it’s lively, fun and compelling.

As has already been mentioned, the Conceptualists were sceptical of the idea that an artist can express himself through art and create something new. Hence, the practice of working through invented characters was widespread.

Komar and Melamid invented two distinct characters and signed their works on behalf of them. One of these personas was the serf Apelles Zyablov, the world’s first abstract artist. He had created the non-objective painting Portrait of Her Majesty Nothing in the 18th century, ahead of Malevich by a hundred and fifty years. The other was a realist painter named Buchumov, who lived and worked at a time when the Avant-Garde prevails. Raging futurists knocked his eye out, but he stayed faithful to the truth of life and the principle of “I paint what I see”, and so all of ‘his’ apparent paintings have a piece of his nose on the canvas.

While Komar and Melamid had just two imaginary co-authors, Kabakov had a whole range of them. ‘Charles Rosenthal’, for instance – a native of Kherson, a student of Malevich and Chagall, who emigrated to Paris and died under the wheels of a car in Montmartre. In the installation Alternative History of Art, Rosenthal is the indirect teacher of another character named Ilya Kabakov, who had the same name as the artist. Another of these fictional authors was the unknown creator of posters for the Housing Office. As Kabakov put it, “before becoming a graphic designer at the Housing Office, he had lived a difficult life, and his art is a strange mixture of shoddiness, lack of skill, and bright flashes, guesses and insights.” For many years, Kabakov signed his works together with his wife, “Ilya and Emilia Kabakov”, another collective character.

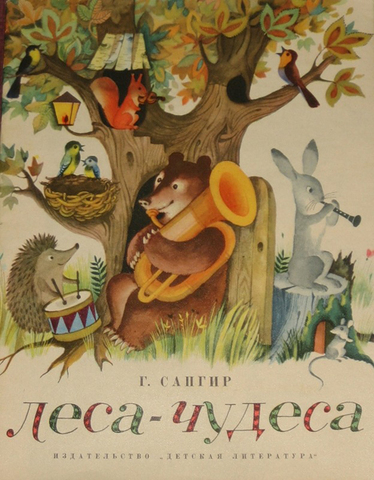

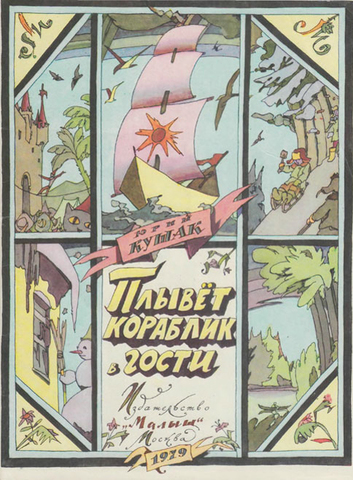

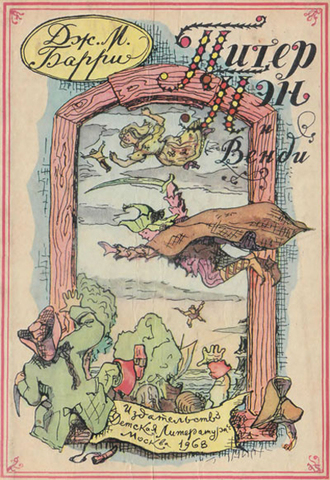

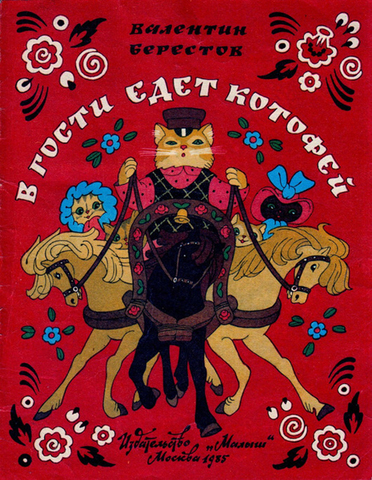

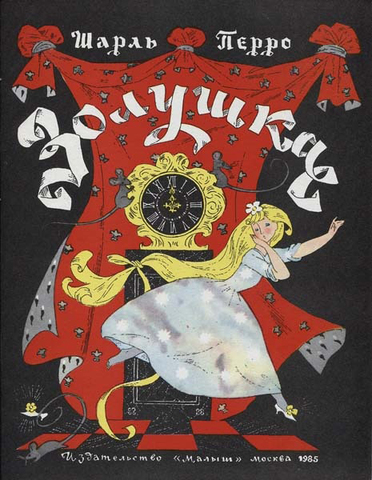

This escape from the clearly defined ‘self’ would even come to receive a special name in the Conceptualist dictionary – Kolobkovost, referring to the Russian version of the Gingerbread Man. It would also have an impact on the personal behaviour of the artists. As a rule, Conceptualists didn’t join protest initiatives; only Melamid and Komar participated at the Bulldozer Exhibition in 1974, hosted by underground artists and broken-up by the authorities. They didn’t count on foreigners buying their work. At the time, such work could not become ‘dip-art’, or art to be sold to international diplomats resident in Moscow – its aesthetic value was questionable, hence the absence of commercial value. Many artists had jobs at publishing houses, particularly in illustrating children’s books – including both Kabakov and Pivovarov, and Bulatov with his co-author Oleg Vasiliev. Their books are of high quality, so there was no painful gap between what was done ‘seriously’ and what was done ‘for money’. However, this wasn’t always the case. There is a wonderful story, perhaps not entirely true, of how either Komar or Melamid had once tried to make portraits for money. They received a commission for a portrait of a distinguished worker, a man with magical hands. The artist made the portrait with all the care of hyperrealism. But in the end he couldn’t resist; he painted the man’s hands golden – and, naturally, didn’t get paid.

We have only touched upon the founders of Moscow Conceptualism, but the movement had a long history. The conceptualist idea was too strong not to affect the art of the following decades.