Russian Avant-Garde

In March 1915, rumour had it that the collector Sergei Shchukin, purchaser of many impressionist paintings, had acquired a work by Vladimir Tatlin at the “Tram V” art exhibition, — a thing made of wooden planks nailed together. A number of researchers have raised doubts about this purchase, but Shchukin never refuted it, despite the wide-ranging coverage of the event. The public was astonished and indignant. One newspaper published a sneering letter about the purchase, for a large sum of money, of something that the author termed “three dirty old planks”. What happened was that Shchukin, a collector with an impeccable eye for such things, had perceived something in this new form of art, so outside his usual sphere of interests.

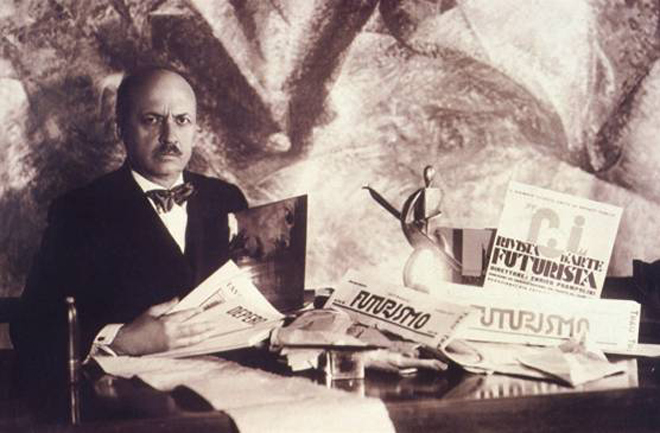

Today, the term ‘Avant-Garde’ has become quite customary, but this wasn’t the case in the 1910s. Back then, the public and the artists themselves used words that either stressed either this art’s oppositional stance, such as ‘leftist artists’, or its novelty and progressive vector. The word ‘futurists’ was the most popular, due to its international use. There were, for example, Italian futurists, whose leader Marinetti even paid a visit to Russia. After the October Revolution, ‘futurism’ was used as a blanket term for all leftist artists. Speaking of the Avant-Garde movement as a whole, the critic Abram Efros wrote that “Futurism has become the official art of the new Russia.”

It is a simple matter to date the appearance of the Avant-Garde to the 1910s. We are also well acquainted with the principal figures of this movement. But it’s rather more difficult to summarise in a few words what the principal idea of the Avant-Garde actually was. There were a lot of abstract Avant-Garde paintings — from Kandinsky’s expressive abstractions to Malevich’s Suprematism — but the Avant-Garde itself cannot be reduced to abstraction. Other artists — Larionov, Goncharova, Filonov, and others — hardly ever deviated from portraying the objective world. As for artistic conditionalism — well, this is not such an easy thing to measure, we are not so easily able to say that this specific point is where the Avant-Garde begins, and everything preceding it is not.

The Avant-Garde was all about the diversity of languages and concepts, both individual and collective. One person’s individual style very often became a group style, as the important artists had their adherents and students. Altogether, this created a certain environment. And it is through this environment and the behavioural norms accepted within it that we can attempt to characterise the Avant-Garde movement.

This was a completely novel type of behaviour — defiant and markedly coarse. There was a certain poetics of impudence to it, a tone exemplified by Mayakovsky. The prime business was, of course, the provocation of the bourgeoisie, whose tastes and attitudes to art, and philosophy of life in general, deserved nothing but a slap in the face. At Saint Petersburg’s Stray Dog Café, frequented by bohemian circles, it was common practice to treat the paying customers with contempt, mocking them as “pharmacists”, even though the establishment couldn’t have existed without them. But the ‘insiders’ were also treated quite unceremoniously.

The leader of the Italian futurists, Marinetti, used to say that the artist requires an enemy — and all of their manifestos were phrased like declarations of war. The history of the Russian Avant-Garde is also a history of quarrels and mutual suspicions. Even in daylight hours, Vladimir Tatlin drew the curtains on his studio windows because he believed that Malevich was spying on him and stealing his ideas. It was all paranoia, of course, but very indicative. Olga Rozanova also accused Malevich of plagiarism. She wrote: “Suprematist art is nothing more than my collages, a combination of planes, lines, disks (especially disks) — and all of it without the addition of any real objects. And after all this, that bastard withholds my name.” Mikhail Larionov had invented the “Jack of Diamonds” name, but both he and his wife Goncharova later rejected the movement. In the early 1920s, Kandinsky initiated the creation of InKhUK, the Moscow Institute of Artistic Culture — and was very soon driven out of it by the Constructivists led by Alexander Rodchenko. The same happened in Vitebsk. Marc Chagall invited El Lissitzky, and Lissitzky invited Malevich — after which Chagall was forced to leave town. Never before had the conflict seemed so total and absolute.

But never before had the currents of art history been so swift. Previously, different movements replaced each other gradually, and even when things had moved more rapidly, the trajectory was still clear. But now, history was galloping ahead. Things that just a moment ago had seemed novel were quickly denounced as backward because, for the Avant-Garde to exist, it always needed a rear guard. The movement existed in a state of constant discovery, and it was extremely important to announce one’s precedence — “this is mine, I came up with this” — to make sure that it wasn’t claimed by one’s rivals. The announcement had to be a manifesto.

The Avant-Garde was a time of manifestos and declarations. Artists wrote them, trying to explain their art and to justify their supremacy and, ultimately, their power. Words became weapons, sometimes a club, sometimes a sledge-hammer. But very few artists could actually write clearly. More often than not, their texts used made-up words in a kind of shamanistic style, occasionally reaching the level of full-on ‘speaking in tongues’. And since the manifesto texts were mysterious, like invocations, their meaning depended considerably on the interpretation of the reader.

All of this tallied with the overall state of affairs, as life itself was then losing its stability, rationality, and certainty. It was no longer subject to the laws of classical mechanics, where an action has an equal and opposite reaction. Now, the parallel lines were inexplicably crossing one another. Anything could be expected from anyone, now that his ‘unconscious’, hidden deep down in the soul, might smother the voice of consciousness. Sigmund Freud’s The Interpretation of Dreams and The Psychopathology of Everyday Life, released in 1900 and 1901 respectively, had forced people to see subdued sexual nightmares even in the carefree days of their childhood. And then the First World War confirmed this new knowledge, completely devaluing the key ideas of traditional humanism. In 1915, Albert Einstein presented his general theory of relativity, giving birth to an era of total relativism. Now, nothing was considered definitively true or absolutely genuine. The artist no longer had to say “This is how I see it,” as he now had the right to say “I want it this way.”

Painting itself, which had previously been satisfied with the traditional notion of a painted canvas as a window to the world, could no longer be satisfied with this. That window could no longer show anything stable — the space behind it was full of cavities and black holes, a fluid world of strange energies. Things had fallen out of their traditional place and broken into fragments, and there was a temptation to put them back together in a completely different way. The new art was trying to experience this world directly, violating the notion of boundaries. The surfaces of pictures swelled up, covered by collages and stickers, and real objects invaded paintings — life itself was invading them. This was later given the name of ‘assemblage’, but for now it was called ‘pictorial sculpture’. Such attempts to unite art and reality had a bright future ahead of them, and this type of art survived all the way through the 20th century. One of its most radical forms was the ‘ready-made’, in which pre-existing objects were presented as artistic works, such as Marcel Duchamp’s urinal, which he called Fountain. But nothing of this happened in Russia. It’s possible that the Russian artists’ global ambitions prevented such gestures. The Russian Avant-Garde had a strong metaphysical flavour, and wasn’t about objects at all.

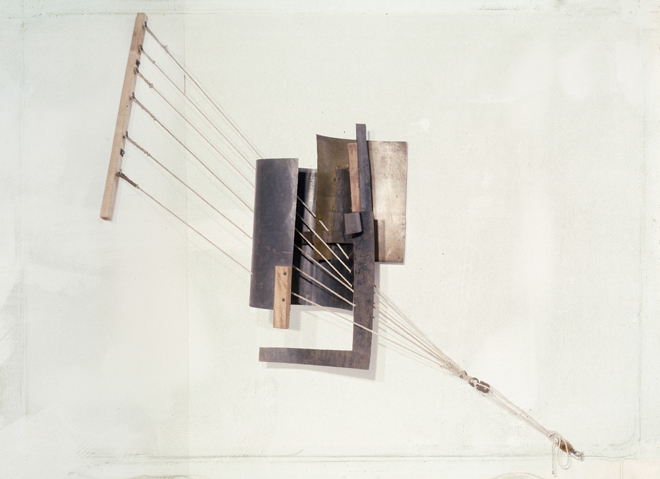

Despite the diversity of concepts, there are two that particularly stand out, not so much for refuting as completing each other. Malevich’s vector was all about bringing a new order to the surrounding world: seeking not to transform art, but to transform the world through shapes and colours. Malevich was without doubt a charismatic man and a great strategist, and he approached his work as a demiurge, a creator intent on transforming everything. But alongside Malevich there were other forms of organic, non-violent Avant-Garde. Artists such as Matyushin, Filonov and Tatlin didn’t want to transform nature, they wanted to listen to it. Tatlin, considered the father of Russian Constructivism, listened to and cherished the voice of his materials. His hollow reliefs, three-dimensional compositions made out of wooden, metallic, and even glass parts attached to boards, were extremely radical in their departure from the traditional painted surface, while at the same time demonstrating an almost Buddhist submission to the natural qualities of wood or metal. There was a legend that Tatlin once kicked a chair from under Malevich, suggesting that he should sit on the abstract categories of shape and colour instead.

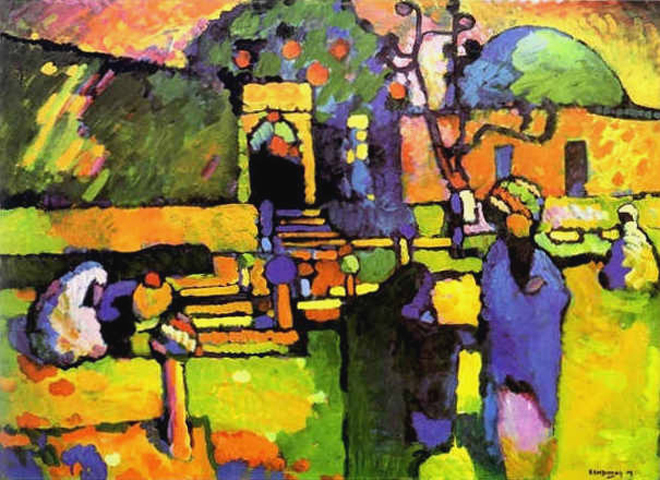

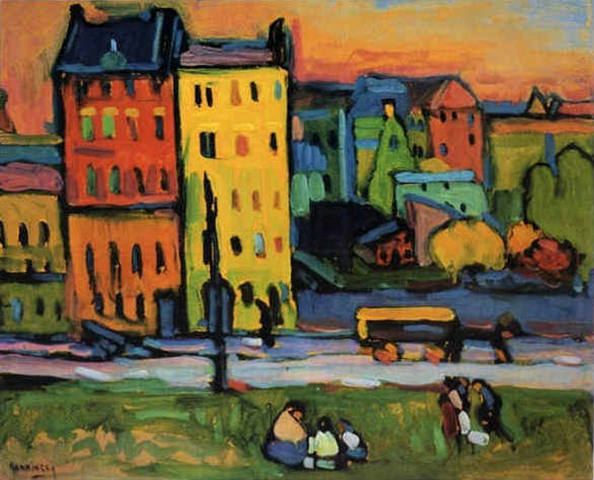

The first Avant-Garde breakthroughs came from the West, not from Russia. The French Fauvism of Henri Matisse, André Derain and others, as well as the early Cubism of Picasso and Braque, all came on stage almost simultaneously, in 1905 and 1906. This was also the year when the first German Expressionist group, Die Brücke (‘The Bridge’), was formed. Later, Larionov, Goncharova, and even Malevich, would experience their own Fauvist period, but on the whole Fauvism didn’t leave a strong mark on Russian art. Cubism, on the other hand, had a significant influence on many artists, but this was mixed with the influence of Italian Futurism, which had evolved by 1909, when Marinetti’s first Futurist manifesto was published. Cubo-Futurism is a Russian word and a Russian phenomenon. Expressionism, signs of which can be found in the works of Larionov and David Burlyuk, was important for Russia, because of the important role played in its establishment by Wassily Kandinsky, who was as much a Russian artist as he was a German one. In 1911, it was Kandinsky who, along with Franz Marc, organised Der Blaue Reiter (‘The Blue Rider’) Expressionist group in Munich.

Kandinsky deserves special attention. He was the pioneer of Non-Objectivity. His Painting with a Circle, of 1911, is considered the first work of abstract art. He divided his abstractions into impressions, improvisations, and compositions. The impressions were inspired by his experience of reality. Improvisations were about letting the unconscious come to the fore, while the compositions were works of careful deliberation. An underlying base of Symbolism was strong in Kandinsky’s work, both in paintings, and in his treatise On the Spiritual in Art. In this text he attempted to describe the effect of different colours on consciousness. “Colour is the keyboard,” — he wrote, — “the eyes are the hammers, and the soul is a grand piano with many strings. The artist is the hand which plays, touching one key or another, to cause vibrations in the soul.” Another artist, Mikhail Matyushin, was exploring the nature of colour in approximately the same vein.

Matyushin essentially gave the first impetus to the Russian Avant-Garde. He was the founder of the Saint Petersburg-based Union of Youth, which was registered in the February of 1910. (The famous “Jack of Diamonds” exhibition didn’t open until December of that year.) Matyushin was much older than all of his comrades, but both he and his short-lived wife Elena Guro were important figures of the Avant-Garde. Matyushin was considered more a theorist and organiser than a doer, which allowed him to keep out of the jealous infighting for supremacy. Matyushin was friends with Malevich, who was sympathetic to the mystical overtones of the former’s quests. And there was a lot of mysticism: Matyushin’s organic concept was based on the belief in art’s ability to become a method for transcending the fourth dimension.

This required the acquisition of expanded visual sensitivity skills, allowing a person to see the world not just with his eyes, but with his whole body. Matyushin’s students once, for example, went to paint a pond near Sestroretsk, but stood with their backs to it while painting. Thus he tried to materialise the metaphor of ‘eyes in the back of the head’. Matyushin was exploring the nature of vision both as a Symbolist and as a systematist biologist. The results of this research were summarised in his Guide to Colour, published in 1932, a rather untimely date for such a work.

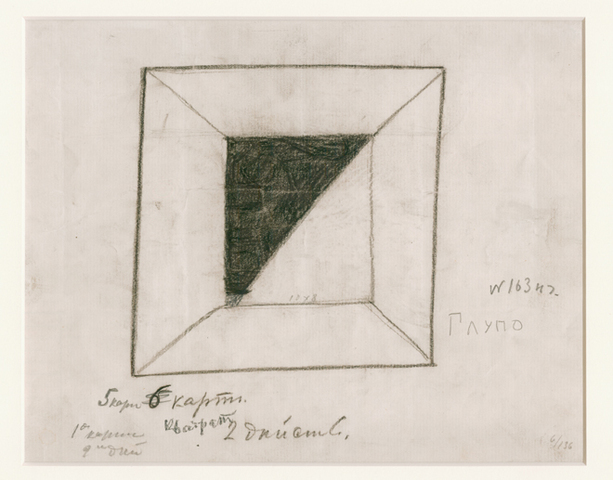

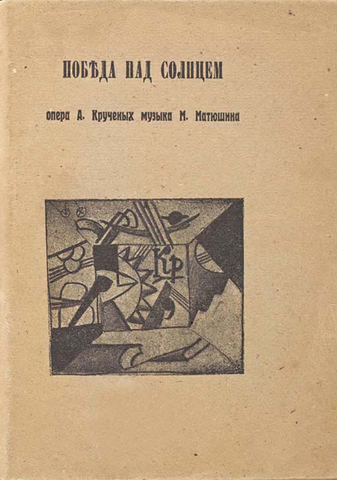

Matyushin initiated another important Avant-Garde undertaking, the 1913 performance of the opera Victory Over The Sun. Himself a professional musician, he wrote the score. The futurist poet Alexei Kruchenykh wrote its disorienting libretto, while Malevich was in charge of the stage sets, in which the black square motif made its first appearance. The plot of the opera is the Futurists’ conquest of the Sun, by means of the black square. Later, in 1920, Malevich’s disciple El Lissitzky attempted to stage the opera in Vitebsk. Under his direction, the opera’s main storyline about the victory of machines over nature was presented in the most direct way possible: the actors were replaced with mechanisms, so-called figurines set in motion by electricity.

As already mentioned, the Union of Youth, organised by Matyushin, was the first Avant-Garde association, albeit with a fluid membership. At that time, however, specific exhibitions were more important than associations, as an exhibition was effectively a manifesto that was seen and discussed. The first such exhibition was the “Jack of Diamonds” in December 1910. The name, thought up by Mikhail Larionov, referenced a whole range of lowly associations, such as cheating at cards and criminal emblems. The ‘Jacks’ — Ilya Mashkov, Aristarkh Lentulov, Pyotr Konchalovsky, and others — were quite happy about this, since their aim was to shock the public.

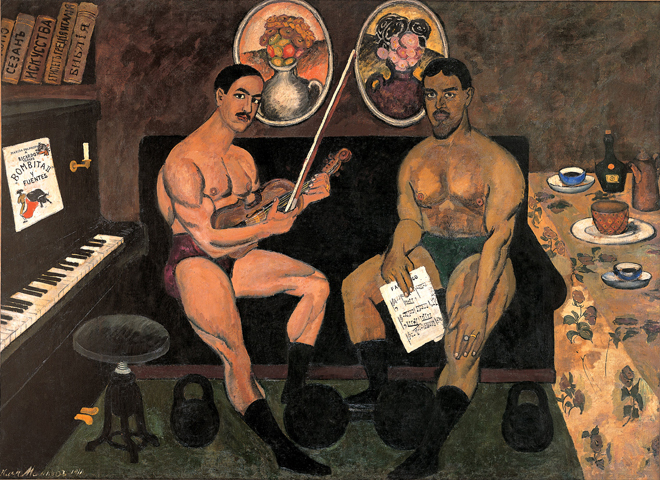

One huge painting at this exhibition, by Mashkov, depicting himself and his friend Konchalovsky as half-naked wrestlers or heavyweight athletes, was absolutely shocking and provocative. At the same time, these athletes weren’t averse to more cultured things: the painting contained a violin, a grand piano, and some printed music. This was the new all-encompassing image of the artist. The cheap popular prints depicted on the walls were an important sign that the Jacks of Diamonds were committed to urban folklore and popular aesthetics, all those shop signs, painted trays and trade fair photo stand-ins. An album of Cézanne’s works on the shelf is another sign — the Jacks adored Cézanne. They understood Cézannism as a simplified geometrisation of the world, for which they used the already familiar experience of French Cubism. All in all, the ‘Jacks’ believed that simplification of forms was the right thing to do. They didn’t believe in getting bogged down in details, but wanted to see things as a whole, as if for the first time. This was exciting, it was a game to be played.

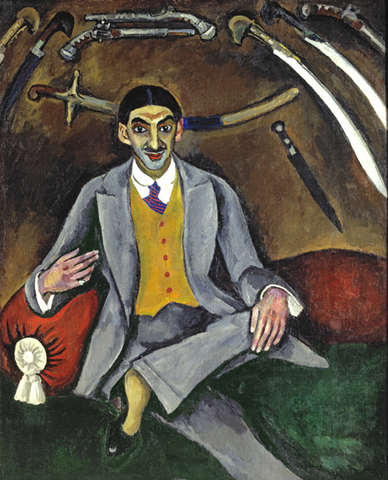

Play is another important word for this collective programme. There was an atmosphere of buffoonery, and the artists cheerfully hid behind various carnival masks. In one of his self-portraits, Mashkov depicted himself as a factory owner, wearing a luxurious fur coat, standing in front of a steamboat. Konchalovsky painted a portrait of another artist, Georgy Yakulov, as an ‘oriental man’. Lentulov painted himself as a red-faced trade-fair salesman. It was also Lentulov who painted the Cubo-Futuristic Moscow, whose cathedrals were taking off and bursting into dance. Lentulov was also the first to use the collages in his art. He glued silver and coloured foil to his canvases, along with sweet wrappers and even tree bark. His paintings included texts, both painted and cut out from posters and newspapers. The paintings themselves overflowed beyond their boundaries, veering here towards reliefs, and there towards abstraction.

The provocations of the Jacks of Diamonds were a dispute with the art of the past, which the Jacks didn’t even consider art, but rather literature or philosophy. For them, art had to be itself, a thing of play and the joy of paint. Their art didn’t reference anything beyond its own limits, and it seemed that there was nothing in the world save for this art. This was an attitude that would be preserved in the Russian Avant-Garde down through the years.

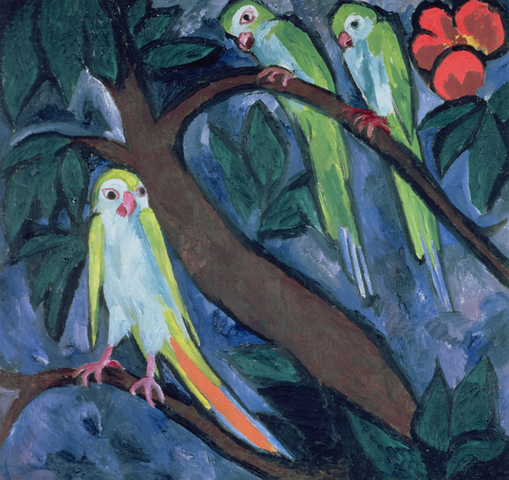

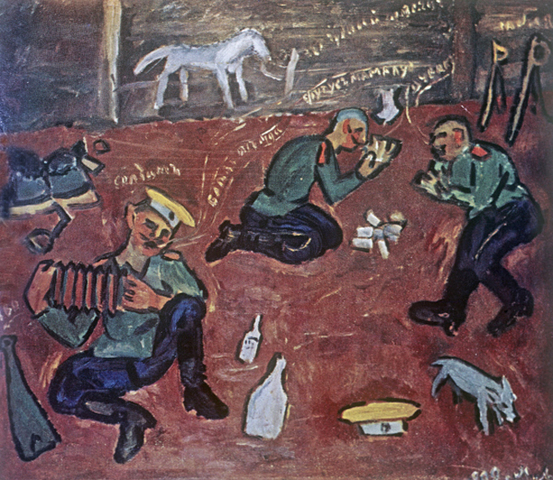

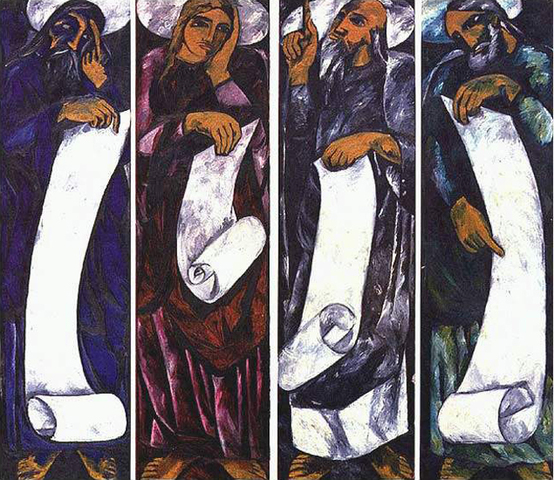

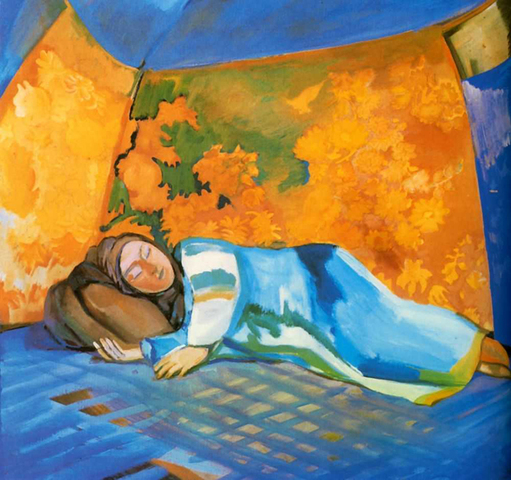

While the Jacks continued to work in their own style even after the first exhibition, Mikhail Larionov was changing the style of his work from one exhibit to the next. The exhibition that followed the Jacks was called “The Donkey’s Tail” and took place in 1912. The name referred to a recent scandal in Paris, where a group of flamboyant artists had presented a painting supposedly executed with a donkey’s tail. At the exhibition, Larionov presented the audience with the Neo-Primitive style. Neo-Primitivism was a system based on the archaic, on ancient and impersonal art. Strictly speaking, this wasn’t the first time that artists had referred to such strata. In the 1910s, Pavel Kuznetsov, one of the principal members of the “Blue Rose” movement, painted the Kyrgyz Suite — a set of paintings about the lives of steppe nomads, undisturbed by civilisation and unchanged through the centuries. But Kuznetsov poeticised this permanence, while Larionov and the other artists who experienced this ‘Primitivist period’ saw this rigidity as something chthonic and ominous. The “Donkey’s Tail” exhibition presented paintings ranging from Larionov’s Soldier and Turkish series, to the Evangelists series by Goncharova, which was removed by the censors, along with Goncharova’s ‘peasant’ paintings, and works from Malevich’s ‘peasant cycle’, and much more. At the very next exhibition, entitled “The Target”, Larionov presented the public with the oilcloth paintings of Niko Pirosmani.

The “Target” exhibition of 1913 was accompanied by the Rayonnists and Futurists manifesto. Rayonnism was Larionov’s version of abstract art — the first in Russia, since Kandinsky had devised his Non-Objectivity in Germany. In the manifesto, Larionov appeared surprisingly close to Matyushin in his mystical and biological reasoning on the nature of sight. A person is looking at an object, but what he sees is a sum of rays reflected from that object and perceived by the eye. The Rayonnists believed that the artists should paint those rays, not the object itself. At that, the object in question may turn out to be somebody else’s painting, and this brings us to another of the manifesto’s theses, the thesis of ‘everythingness’ or ‘all-ism’. Every artistic style is useful to the modern artist, Larionov said, and every style can be appropriated and reshaped. The artist is obliged to change, because the world itself is changing rapidly, and the artist should react to those changes. The “Target” exhibition presented all kinds of art at once — both the Rayonnist abstractions that still contained a hint of figurative motifs (such as the bird heads in the Cockerel and Hen painting), and Primitivist works. The most radical of the Primitivist works was the Seasons series, inspired both by cheap popular prints and by children’s drawings. Adhering to the concept of ‘everythingness’, Larionov did not limit himself to the combination of Primitivist with Rayonnist works. He also became the inventor of new practices, such as futuristic face painting, futuristic cuisine, and futuristic fashion. Many of the concepts remained theoretical, but the futuristic face painting — the abstract painting of faces inspired by Rayonnism, was actually brought to life.

In writing his Rayonnists and Futurists manifesto, Larionov, a militant and bellicose man, claimed that he wasn’t fighting with anyone because he had no worthy adversaries. Malevich wasn’t an adversary, but a brother-in-arms who took part in Larionov’s exhibition. His own movement of Suprematism, which also contended for primacy in the artistic hierarchy, didn’t take shape until after Larionov left Russia.

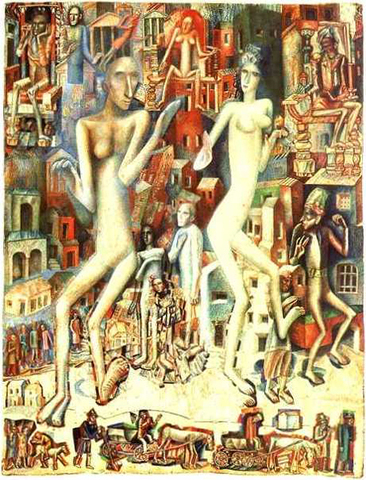

Malevich’s road to Suprematism was actually a rather intensive procession through various different stages. Malevich began with Impressionism, just like Larionov and, to a certain extent, Kandinsky. After that, he engaged in Neo-Primitivism, followed by Cubo-Futurism and Alogism. His alogist painting Englishman in Moscow portrays a green man in a top hat surrounded by a sabre, a candle, a herring, a staircase, and the phrases “partial eclipse” and “racing society”. This was the poetry of the absurd, artistic ‘sophistry’, a collage combination of incompatible objects and texts within a single painting. Malevich got rid of the cause-and-effect order, and this step made his Alogist paintings the analogue, albeit an incomplete one, of the works produced by Western art’s Dadaists.

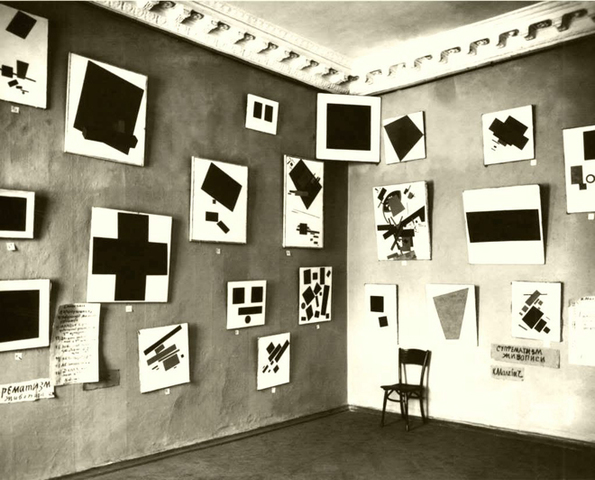

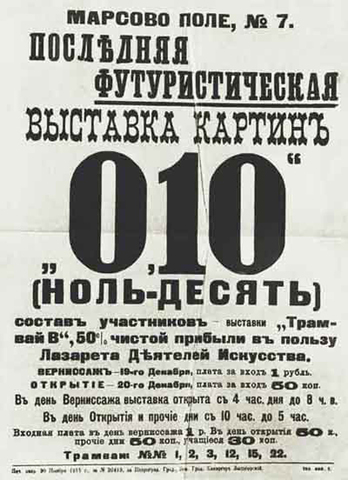

For Malevich, the ‘alogisms’ were just a stage before the final phase of Suprematism. This style emerged in 1915 and was presented in December of that year at the last Futurist exhibition, entitled “Zero, Ten”. The zero in the exhibition’s name signified the end of art, the “nullity of forms” announced by Suprematism and symbolised by the Black Square. The number ten was supposed to signify the number of participants, though in reality there were more artists involved.

Suprematism was geometric abstraction. For Malevich, geometry was a metaphor for totality. The whole world was reduced to a set of geometrical signs, and there was nothing else. In 1919, Malevich organised his own personal, summarising exhibition, from his earliest Impressionist paintings to the latest Suprematist ones. He even repainted a number of works that hadn’t survived from the earlier years of his career. The exhibition was completed by a row of empty canvases stretched onto underframes, stating thereby that painting was finished. Suprematism was its highest point, which annulled anything that might follow.

Nonetheless, Suprematism was, from the very start, offered up for exploration by other artists as well, and was taken up by several. In this, it was unlike the expressive abstraction of Kandinsky, which did not find immediate followers as a distinct programme or school. In 1920, while at Vitebsk, Malevich established the UNOVIS art community, whose acolytes were to paint in the very same style as their guru, and to hold anonymous and collective exhibitions of Suprematist art. It was assumed that there was no place for individual artistic expression of will in Suprematist art, only the confirmation of a system aspiring to universality and seeking to be the final inventory of everything in the world and the last word on it. The word supremus in the name of the movement meant ‘the highest’, and this was the last word in art.

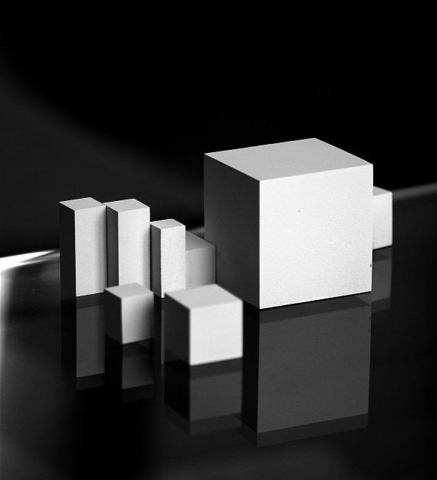

That said, this universal language well suited several future projects. Malevich and his students — Ilya Chashnik, Nikolai Suyetin, and Lazar Khidekel — used Suprematist forms to propose a new kind of architecture. They created ‘architectons’ in plaster and drew ‘planitas’, model dwellings for Earth-people in the universe of the future. The architectons were abstract, devoid of windows and doors, and their internal space wasn’t dealt with at all. Malevich wasn’t interested in functions, only in absolute forms, the utopian modules of a new order. His dishware, created in the early 1920s when he collaborated with the Lomonosov Porcelain Factory, wasn’t predisposed for everyday use either. It was difficult to pour tea from a Suprematist teapot, and drinking from the half-cup was inconvenient. These things were a manifestation of form, and the form was self-sufficient.

In the 1920s, the idea of productive, industrial art became a justification for the Avant-Garde search for new forms, an idea we shall discuss shortly. But the principal artists of the pre-Revolution Avant-Garde movement had a difficult time with this idea. This was true even for those who were willing to dedicate themselves to the production of functional things ‘for life’, such as Tatlin. His dishware and ‘normal-clothes’ turned out alright, but the ‘great projects’ remained a utopia. The incredible ornithopter Letatlin (a word combining the artist’s surname and the Russian for ‘to fly’ — letat) never flew. The Monument to the Third International, otherwise known as “Tatlin’s Tower”, was never realised. After all, it was difficult to believe that the grandiose idea of a high-rise revolving structure could actually be fulfilled. Tatlin didn’t like the word ‘Constructivism’, and as a general rule tried to avoid any kind of ‘-ism’, but was still considered the ‘founder’ of this movement, being the first artist to have started making things instead of painting them. There’s a photo of George Grosz and John Heartfield that shows the two German Avant-Gardists holding a placard that says “Art is Dead — Long Live Tatlin’s Machine Art.” But in reality, the ideas of ‘proper’ machine Constructivism were declared and carried out by other people, such as Alexander Rodchenko.

Rodchenko was one of the most productive second-generation Avant-Garde artists, and one of the most consistent ‘production men’. His heyday coincided with the post-revolutionary period. At first, he seemed to be taking the next steps on a road already explored by his elders — moving towards a greater conciseness, and, subsequently, greater radicalism. Malevich’s geometric forms were dense, while Rodchenko used thin lines, and called it Linearism. He even wrote a manifesto on the potential of lines. Tatlin’s hollow reliefs were connected to the wall, while Rodchenko’s mobiles hung freely in the air. His experiments had no metaphysics behind them, which is why all of his discoveries easily became the ABCs of industrial design. Rodchenko was equally successful as a book illustrator, poster artist, stage and interior designer, furniture maker and photographer. His photomontages and techniques for angle shots became the visual symbol of those times. It wasn’t by chance that he initiated Kandinsky’s expulsion from the Moscow Institute of Artistic Culture. This was a confrontation between the new materialistic approach to art and the old, conceptual one.

Moscow’s INKhUK, as well as the Leningrad-based GINKhUK, two institutes for artistic culture, aimed to develop universal methods of dealing with form. After the October Revolution of 1917, the search for universals was widespread, and Avant-Garde artists played an active part in the work of various educational institutions, of which there were suddenly many. One could say that they were implanting their beliefs. Kandinsky believed in a synthesis of arts supported by biology, physicality, and synaesthesia. He believed that this synthesis would be achieved on the basis of three arts — painting, music, and dance — and those were the subjects he offered for study. But for the young artists headed by Rodchenko, all of this was redundant and out of step with the historical moment. How can one study dancing, when there are problems with the production of bare necessities? This should be the artist’s objective. Naturally enough, Rodchenko and his group won this dispute hands down, but their victory was short-lived. Very soon, those bare necessities would be produced without any Constructivist spirit at all. We’ll speak of those who vanquished the Constructivists in our next lecture.