The Thaw and the 1960s. The Birth of the Underground

The cultural epoch of the ‘Sixties’ commenced before the start of the decade itself. Stalin’s death, the denunciation of his personality cult by Nikita Khrushchev, and the rehabilitation of political prisoners had already taken place in the 1950s. Ilya Ehrenburg’s novel, which gave the name to the era known as Khrushchev’s Thaw, was published in 1954, and the major changes were announced at the 20th Congress of the Communist party two years later. It all came to an end – speaking specifically about art – in the December of 1962, when Khrushchev lambasted an exhibition at the Manège, destroying all hopes for artistic freedom. The ‘thaw’ lasted for a brief period of six years, from 1956 to 1962. This period also had its ambiguities – the persecution, for example, of the writers Boris Pasternak and Vasily Grossman. Freedom was unstable and shaky – but it was there. This transient moment of lightness generated a momentum that lasted throughout the 1960s.

The art of the Stalin era gave the impression of a giant frozen monolith. Suddenly this monolith was subjected to a new warmth and began to melt and disintegrate. Artists were now, first of all, free to explore different artistic currents and establish relevant points of reference. Their exploration stretched out across two dimensions: the temporal, by which artists revisited the highlights of Russian art history, especially the Avant-Garde, and the spatial, involving study of contemporary art movements in the West. In both respects, their search was, to say the least, limited.

Those surviving artists who had witnessed the Avant-Garde, received frequent visits, pilgrimage-like in nature, from members of the younger generation. Especially popular were Favorsky, Falk and Fonvizin – the three ‘F’s. The first apartment-based exhibitions – for example, the home viewing salons of George Costakis’, an avid collector of the Russian Avant-Garde, – were organised . News from the West came from America magazine, which returned to the presses in 1956 by permission of the Soviet authorities. The same year saw the first Picasso exhibition in Moscow. This was possible thanks to the artist’s own communist stance, and made a stunning impression. In 1957, an abstract art exhibition formed part of the World Festival of Youth and Students. The American National Exhibition of 1959 in Sokolniki Park featured works by the abstract expressionists Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko, Willem de Kooning, and surrealist Yves Tanguy. Two years later, a similar French exhibition presented the work of Yves Klein. Clearly, there was considerable choice and variety.

This freedom ended abruptly in December 1962, when General Secretary Nikita Khrushchev visited an exhibition at the Moscow Manège marking the 30th anniversary of the Moscow Union of Artists. There, alongside Socialist Realist works, Khruschev encountered the new Soviet modernism and he erupted in anger. He declared to the artists that their work was “shit” and “scribble-scrabble”, and called them “damned faggots.” This incident triggered a fresh crackdown on art. The illusion that Soviet art could be both independent and public was shattered.

And here the art scene fractures. On one side are those who expect publicity and are open to compromise, on the other – those who desire complete freedom and are forced to go underground. The notion of ‘underground art’ emerged, also referred to as ‘non-conformism’, ‘the other art’, or ‘the second Avant-Garde’. At this stage the division was rather relative and not fraught with personal confrontations, though these would nevertheless soon surface. Gradually, the underground scene developed its own peculiar structure and its artists began to divide into groups.

Initially, these groups were not built on the principles of shared artistic values, but on the plane of shared living circumstances, such as joint military service, kinship, being close neighbours, and professional relationships. Consisting of the members of one large family and their friends, the Lianozovo group was founded on blood ties. There were the elders of the family – Yevgeny Kropivnitsky and his wife Olga Potapova, their children – Valentina Kropivnitskaya and Lev Kropivnitsky, and Valentina’s husband Oskar Rabin, who eventually became the main figure of this circle. Their close friends were the artists Vladimir Nemukhin and Lydia Masterkova, poets Genrikh Sapgir, Igor Kholin, Yan Satunovsky, and Vsevolod Nekrasov.

The Sretensky Boulevard group, formed in 1969-70, was founded more on the basis of geographical proximity. Ilya Kabakov, Viktor Pivovarov, Erik Bulatov, and Ivan Chuikov all had studios in the same area of Moscow. This was one of the breeding grounds for Conceptualism in Russia, which we will discuss separately. It’s important to note in this case that the initial matter of being simple neighbours evolved into the founding principle of a real artistic school.

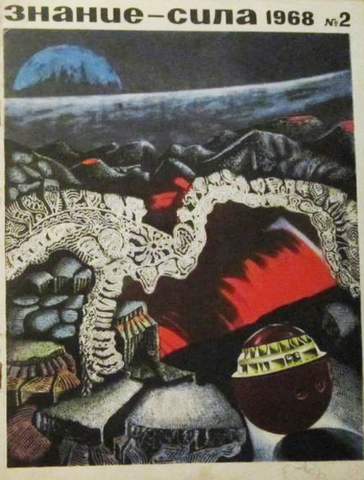

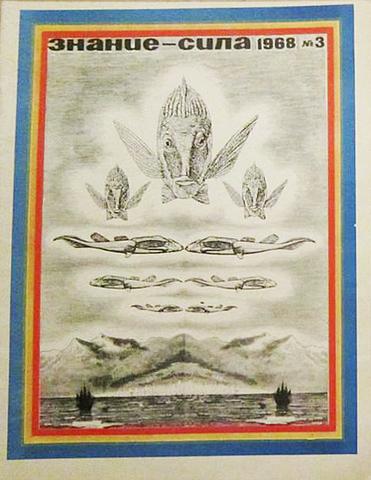

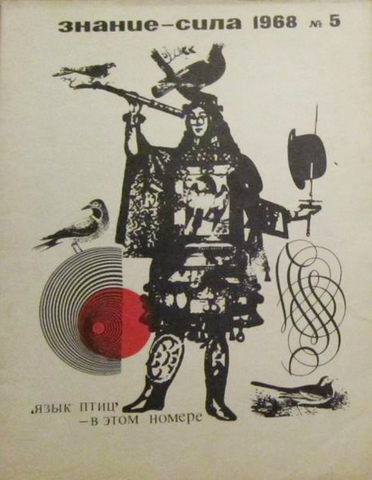

There was also a circle of co-workers, that formed around the magazine Znaniye – Sila (‘Knowledge is Power’). Yuri Nolev-Sobolev became its art director in 1968 and received access to administrative resources, albeit limited, in scale. He involved all the underground artists in the magazine’s work. Well, maybe not all, but as many as he could. Sobolev wasn’t a member of the Party and didn’t divide his colleagues into friends and foes. As such, Vladimir Yankilevsky, Ernst Neizvestny, Viktor Pivovarov Ilya Kabakov, Boris Zhutovsky, Anatoly Brusilovsky, and Ülo Sooster all worked with him, along with many others. As the name of the magazine might suggest, its core essence was technocratic, with occasional forays into science fiction. The very nature of the magazine thus encouraged all manner of artistic license, occasionally of a surrealist bent: it was less about life than about inventing things, about futurology. In general, it provided space and a multitude of opportunities for experimentation.

As for this ‘multitude’, it is important to note that everything, from genres to techniques, was being reclaimed all at once. Socialist Realism had been an era of cultural famine, and suddenly the world was opened up again; not in the form of a book with linear narrative, but in the form of a Möbius strip. Past and present, the heritage of the Russian Avant-Garde and Western art were all mashed together on a single surface. This information needed to be untangled and staked out, and Russian art, generally speaking, needed to ‘catch up’ with the world and make up for lost time.

In fact, this paradigm of catching up and making up has been something familiar to Russian culture since the early modern period, since the times of Peter the Great, to be precise. After all, while the West was undergoing the Renaissance, Mannerism, the Baroque, the Age of Discoveries, and the development of science, Russian life passed by in log cabin izbas and richly carved wooden terem palaces. Then Peter I suddenly disrupts the status quo, pushing the country towards Europe, which doesn’t go smoothly because Russia knows and understands nothing about the European ways. In Europe, art existed in a variety of genres – while in Russia, for instance, portraits were feared because depiction of the soul was believed to attract the devil. Throughout the 18th century, Russia was bridging this divide quite rapidly, skipping some stages, and hurriedly stitching others together. Correlation of our culture with the Western European might only really be considered to have been more or less achieved by the time Catherine the Great came to the throne.

Something similar took place in the second half of the 19th century. First the Peredvizhniki (or ‘Wanderers’) movement somewhat corresponded to the realist trends in Western painting. But in Europe, changes happen more quickly – Impressionism was soon replaced by Post-Impressionism and the Decadent movement. And we were left with dull genre painting right up until the early 20th century. But then everything changes instantly: an express Art Nouveau, and express Avant-Garde. Once more, we caught up with the West and even surpassed it.

The 1960s follow the same pattern. For instance, we needed to catch up with abstract expressionism. So all the elements of American and French post-war abstract art, and even early Pop Art, were all blended together into one; not as successive (and opposing) movements, but as something coeval and co-existing.

In this regard, it was characteristic that underground art groups formed on the basis of friendships were not schools. The Lianozovo group is often referred to as a school in hindsight, but it wasn’t one: nothing was taught there. This could have happened, though: the group’s members were of different generations, and Yevgeny Kropivnitsky, for example, had witnessed Futurism, and even been involved in it. However, everyone felt equal, and contemporary art, which was new to every member, was studied collectively; like an introductory course, it covered abstraction, surrealism, expressionism – all mixed together.

The only real school functioning in the underground milieu during the Thaw was the studio of the brilliant teacher Ely Bielutin, who taught abstraction and called for spontaneity and liberation of the artist’s hand. Bielutin is a largely mysterious figure: a mystifier, collector (his collection included Titian, Rembrandt, El Greco), and a member of the aforementioned Manège exhibition, which had so enraged Khrushchev and prompted him to state: “The Soviet people do not need this.”

But when we talk about the new Russian abstract art of the time, it is not the many Bielutin students that come to mind, but other very different people.

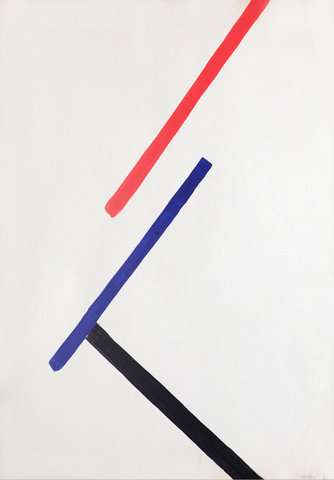

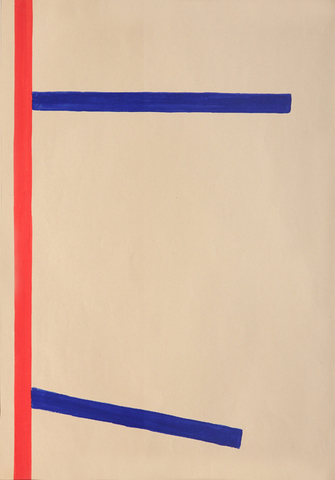

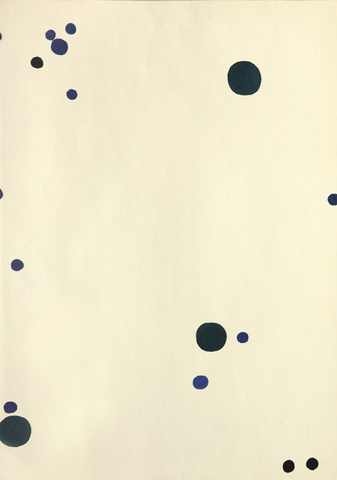

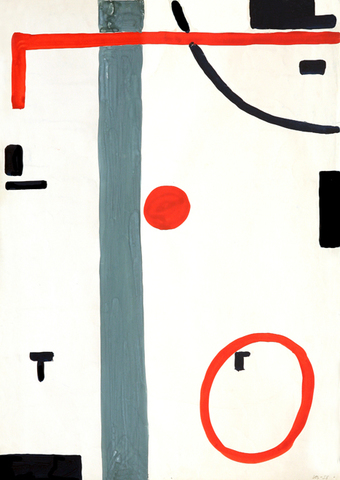

Yuri Zlotnikov, for example. In the 1960s, he created the series Signalnaya Sistema (or ‘Signal System’). This belongs to abstract minimalism: multi-coloured dots, intersecting and self-contained lines, and elementary geometrics. This “Signals” was conceived as a scientific paper, and a study of the effect of paintings on people in an attempt to create, according to the author, “the model of our sensory experiences”. Zlotnikov used the methods of mathematics, cybernetics and biological current theory. And it really was a system that aspired to become a universal language – a claim that could level with that of Malevich, Suprematism, and the first Avant-Garde. Zlotnikov really dreamed that spaceships would be decorated according to his system. Then it seemed possible and attainable.

Zlotnikov is usually remembered alongside Vladimir Slepyan and Boris Turetsky. Retroactively, they have been defined as a group which wasn’t really the case, though they shared a strong friendship. Few works by Slepyan have survived: he emigrated in 1958, and abandoned painting for writing in 1963. Turetsky moved from the most fascinating abstractions of the 1950-60s to assemblage – compositions of objects glued onto a plane – as well as to expressionist, but figurative painting. The Leningrad-based artist Yevgeny Mikhnov-Voitenko deserves a mention here too. In the late 1950s he created The Tyubik (or ‘Tube’) Series of Paintings – abstract canvases, onto whose continuous field of zigzags, dashes and notches he placed fragments of objects and writing, handprints, and so on. This was very much in tune with what, say, Jackson Pollock and Yves Klein were doing, of whom Mikhnov-Voitenko hardly knew anything.

And this reinventing of the wheel was wonderful; their wheels were quite radical, and made without reference to specific examples. It was in the 1960s in Russia that the first works that would later be labelled ‘objects’ were created. These were Mikhail Roginsky’s Red Door (a painting of a red door, but with a real door handle sticking out), and The Wall (a picture of a wall with an electrical socket sticking out). Roginsky also painted Mettlach Tile – purportedly a geometric abstraction but in fact a picture of floor tiles. This was classified as Russian Pop-art, although Roginsky himself was against such a categorisation.

Overall, it would be impossible to list all the artists who created their own systems, their own fully independent languages, in this period. The metaphysical still-life paintings of Dmitry Krasnopevtsev, the symbolic surrealism of Vladimir Yankilevsky, Oskar Rabin and his pop-art pomoiki (‘rubbish dumps’) where real objects were imprinted onto colourful canvas, and so on. The first conceptual works of Ilya Kabakov appeared at the same time.

And this was real freedom; the freedom that people talked about. ‘Freedom’ was the main and most important word. And it didn’t really matter that the freedom to have one’s own voice was not necessarily connected to the freedom of personal behaviour, or dissent. That would become more significant later, when division into friends and foes would take place within the underground community. Only then would it truly matter whether someone took part in protest initiatives, like Oskar Rabin, or was looking to make a profit from art-making, or indeed if they worked as a rigger, like Rabin again, while at the same time selling his art to foreigners. (Later, the sale of art works to diplomats, the main buyers of non-conformist art, would be stingingly labelled ‘dip art’). In the meantime, in the 1960s, the word ‘freedom’ had a broad and light connotation. In this sense, it is necessary to talk about the heroes of that time who personified this understanding of freedom, then and later on too.

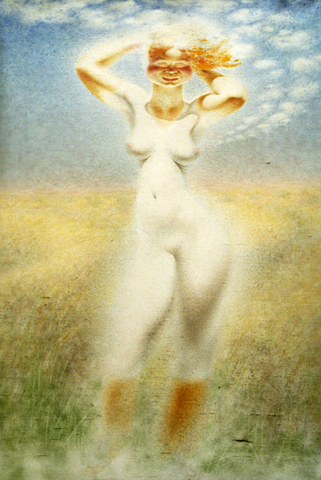

We will start with Anatoly Zverev. A legend of a man, about whom it’s often unclear which tales are true and which aren’t – and it shouldn’t matter. There was a plethora of myths surrounding his persona: the myth of an artist who lived utterly carefree and for his art, an artist of natural talent who had allegedly never studied (this is most likely not true), an artist who sang like a bird and drank like a horse (and this is true) which did not stop him from creating brilliant portraits with a single stroke of a brush. The single brush stroke was a very important notion. Freedom was understood as an immediate inspiration, the instantaneous release of energy. Zverev’s works are extremely unequal in quality, but they all manifest an artistic gesture and for that they are glorified.

The second living legend was Vladimir Yakovlev. He also conformed to the sought-after romantic myth of the artist, in this case a tragic figure, whose mental illness and worsening eyesight sharpened his spiritual vision. He spent his last years in an asylum and there, in the lowest tiers of the underworld, he would bring the paper up close to his eyes and draw alien flowers that seemed to open up with all their being.

Generally speaking, legends were always apt to form around lone artists. These might range from myths about the bohemian artist – as with Zverev, to those of such piercingly vulnerable artists such as Yakovlev, or the myth of the ascetic hermit, or mystic – as in the case of Dmitry Krasnopevtsev.

There were other mythological figures, Vasily Sitnikov, for example (also known as Vasya the Lamplighter, or Vasya the Russian Souvenir), who applied his great talents to building the legend of his own divinely-inspired foolishness for Christ. Stories went round about Sitnikov speaking a strange language, or of sleeping in bandages to escape bedbugs and cockroaches, but then collecting them and setting them free in official establishments – the American Embassy, in particular. Then again there were tales of him teaching – almost exclusively female – students through either shock therapy, or Zen Buddhist rituals. None of his works confirm these anecdotes – above all, they demonstrate masterful technique and reveal an explicit targeting of foreigners, who were his main buyers.

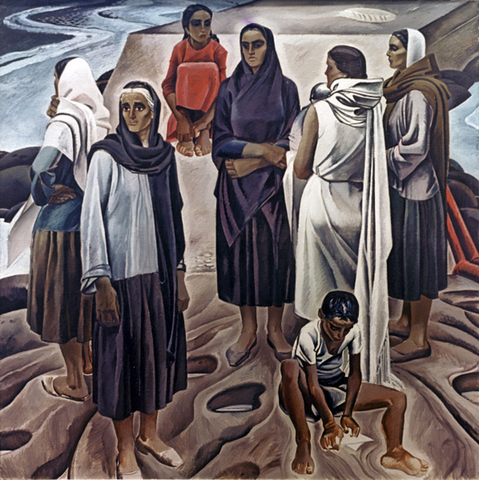

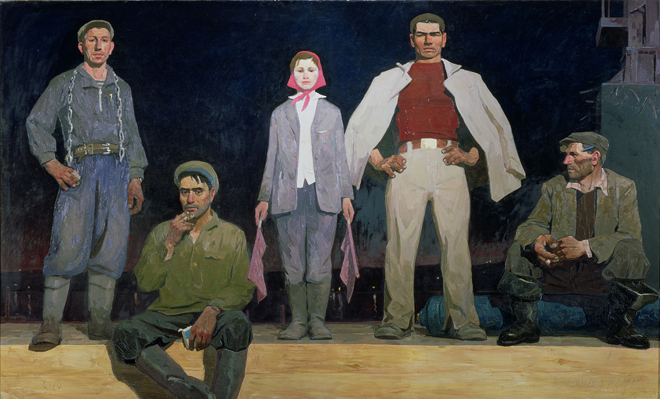

So far we’ve only covered underground art. But the 60s were not only about this – there were artists who preferred to stay in the public eye while still searching for new languages and forms. Their oeuvre was later classified under the title of the ‘Severe Style’. This was a collective style, although the artists did not form a group. Gely Korzhev, Viktor Popkov, Tahir Salakhov, Pavel and Mikhail Nikonov, Nikolai Andronov – together these artists protested against the guiles and grandiosity of the socialist realism of both the Stalin era and its later saccharine incarnation. They stood against didactics, philistinism and the universal adoration of family values. Yes, they were looking for a new language, but mostly they were looking for new subject matter and heroes.

These new pictorial heroes were brought to us in static and poster-like poses. They are not portrayed in action – we see them simply lining up together, as a group. These heroes are tough and rugged men – boatmen, repairmen, miners, or the builders of Bratsk. Women in these paintings are also ascribed a masculine courage and severity, like, for example, in Tahir Salakhov’s Women of Absheron. Works by these artists speak the same language, and it’s impossible to tell one author from another. On the one hand, this style gravitates towards poster art, with such features as generalisation and chopped planes, and on the other, it is reminiscent of the early works by Deyneka and the Society of Easel Painters.

Since the Severe Style revolved around figurative painting, and not abstraction, the artists’ expectations of publicity were seemingly justified. But this didn’t exactly prove well founded: at the Manège exhibition, Khrushchev was as outraged with their work as he was with the Avant-Garde – his taste was for the most primitive socialist realist, and socialist realism was still in favour. So these new characters existed roughly for only three years – from 1959 to 1962, after which their authors each began to work in their own way, and most of their subsequent careers in Soviet art were successful.

Collective platforms in underground art started to appear a little later, in the 1970s, the most interesting and long-lasting of which was Moscow Conceptualism. But at the turn of the decade, even before any groups began to take form, a confrontation would arise between those who would later make up the conceptualist circle, and those who wouldn’t belong to any circles at all, but would insist on the uniqueness of their own way and language.

Conventionally, we call the latter ‘metaphysical’ artists – though the only thing they had in common was their focus on art as a spiritual quest. For them, their work almost constituted a sacred act, “the recovery of truth”. This category includes many, Vladimir Weisberg, for example, who would soon go on to invent the concept of ‘invisible art’ and ‘white on white’, and Mikhail Shvartsman, who didn’t consider himself an artist, but a medium or prophet who hears the voice of God. It might seem that such a position would mean a complete rejection of individualism in artistic practice. However, individualism was blown out of all proportion in his practice. For example, he had a very specific manner of displaying his work: one could only get to see it on personal recommendations, which were very carefully considered, and the shows themselves usually resembled shamanic rituals.

The Conceptualists, on the other hand, sought no truth, and any claim to possess the truth was seen as an imperious infringement, deserving only of playful deconstruction. The Conceptualists therefore mocked the Metaphysicians. Much later, in 1983, Natalia Abalakova and Anatoly Zhigalov, Conceptualists of the first generation, made an installation called KITCHEN ART, OR THE KITCHEN OF RUSSIAN ART, parodying the pomposity of metaphysical art. This is what it looked like: a kitchen, where an oven had dukhovka written on it (literally ‘gas stove’, though the word could also be figuratively understood as a ‘container of the spirit’, from Russian dukh – ‘spirit’); a shelf, covered with curtains, labelled with a note saying sakralovka (‘container of the holy’); and on the shelf with condiments – netlenka (‘container of the eternal’).

Despite the apparent opposition, the different conceptualism groups had much in common. It was Boris Groys’ seminal article Moscow Romantic Conceptualism, published in 1979, that pointed out the impossibility of creating an abstract painting in Russia without referencing the New Testament’s Light of Mount Tabor. And these metaphysical elements, such as alluding to emptiness, blankness and the Tao, would be very important for many conceptualists. We will discuss this in the next chapter.