Artistic Life in the Soviet Union after the October Revolution of 1917

In 1921, the artist Konstantin Yuon, previously famous for his landscapes and depictions of church cupolas, presented his New Planet painting to the public. It depicted a crowd of tiny people, actively gesticulating and watching the birth of a giant crimson sphere. Not much later, the same crimson sphere had appeared in a composition by Ivan Klyun, a comrade of Malevich. The same sphere could be seen in the painting Midnight Sun by Kliment Redko, and it was also held aloft by the muscular arms of the Worker in the painting by Leonid Chupyatov, a student of Petrov-Vodkin.

This coincidence of motifs in the works of very different artists is telling. Everyone sensed that the changes taking place were on a planetary scale, but nobody really understood the artist’s role in this new world. This wasn’t just the personal interest in finding a paying job; it was an essential question about the new function of art.

Many things seemed to be the same – artists were joining up and falling out with each other, they issued thundering manifestos, organised exhibitions, and moved between different artistic associations. But after the Revolution, the familiar universe around them acquired a new and very active protagonist, the state. The state had power, and possessed multiple means of encouragement and punishment, such as state purchases, the organisation of exhibitions, and various forms of patronage.

And this situation was unusual, since before the Revolution, the state never paid much attention to matters of art. Emperor Nicholas II had given some money for the publication of the Mir Iskusstva magazine, but he did this only after being specifically asked to do so. It’s unlikely that he read the magazine himself. But now, the authorities planned to dominate in all spheres of life, and to do it as they saw fit.

Which is why, running ahead a little, it was completely logical that, in 1932, the state issued a decree banning all artistic associations. It’s impossible to rule over things that move and transform by themselves. Flourishing complexity is good, of course, but it too often resembles a free-for-all outside a bar. If everything is made uniform, animosities will be ended and it will be easier to control art.

We’ll speak of the animosities later, but now we shall turn to the presence of an external force, namely the state, and the way it changed the conditions of the game. The group manifestos, which had previously been addressed to the city and the world, and which looked quite outrageous, now had a specific recipient. The artists’ statements of their readiness to reflect the new, revolutionary ideas in their work very quickly began to resemble ritual incantations, because this was what the state demanded without fail. All in all, these were no longer manifestos, but more like declarations of intent, submitted to the management. The majority of artists were sincerely ready to serve the Revolution, of course, but they wanted to do this using their own artistic devices and according to their own notions.

Speaking of post-revolutionary artistic associations, let us begin with those that more resembled schools than communities. These typically formed around some prominent artist or teacher, a guru of sorts, and included his students. Such schools could be actual educational enterprises, such as that of Petrov-Vodkin, which operated between 1910 and 1932, but others were fashioned as artistic associations.

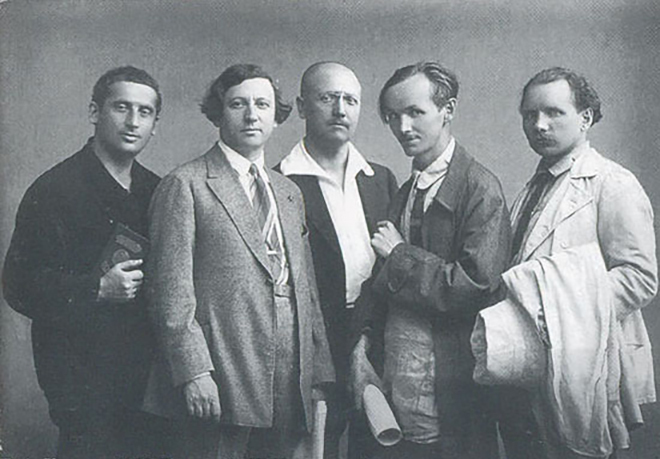

One of them was UNOVIS (an abbreviation for ‘Champions of the New Art’) – the association of Kazimir Malevich’s students, which operated in Vitebsk from 1920 to 1922. This was an actual association, with a manifesto written by Malevich, with exhibitions and other team building events, and its own rituals and attributes. UNOVIS members wore armbands bearing an image of the black square, which likewise adorned the organisation’s seal. The association’s ultimate goal was for Suprematism to play the role of a global revolution, spreading out across Russia and the entire world, to become a universal language. Artistic Trotskyism, as it were. After abandoning Vitebsk, the members of UNOVIS found refuge in the Leningrad-based GINKhUK, the State Institute of Artistic Culture, a scientific establishment.

The school of another Avant-Gardist, Mikhail Matyushin, was also an association, albeit a strange one. In 1923, Matyushin established a group called Zorved, the Visiology Centre, whose manifesto read “Not art, but life.” The group sought to expand the field of vision and to train the visual nerves in order to shape a new way of seeing. Matyushin dedicated his whole life to this, but it was obviously not something that preoccupied the country in those years. Nonetheless, in 1930, Matyushin and another group of his students organised the KORN group, the Collective of Expanded Observation, and managed to organise one group exhibition. The works of Matyushin and his students were reminiscent of biomorphic abstractions. Theory for them was much more important than practice.

In 1925, the school of Pavel Filonov was also granted artistic association status. It was called ‘Masters of Analytical Art’, abbreviated as MAI. The ‘Masters’ had no special manifesto, using Filonov’s previous texts as their guide, including his Made paintings, 1914 and the Declaration of Universal Flowering of 1923. These texts presented Filonov’s method of analytical processing for each of a painting’s elements, which had to result in a specific formula. Many of Filonov’s works were even named in this fashion – Formula of Spring, Formula of the Petrograd Proletariat, and others. Filonov later left the MAI, but the school survived until 1932; without a leader, but in accordance with his legacy.

But none of these schools and associations that gathered around the central figures of the old, pre-revolutionary Avant-Garde were at all mainstream any longer, despite Abram Efros’ observation that the Avant-Garde “had become the official art of the new Russia” being very much on point in describing the situation of the early 1920s. The Avant-Garde movement really was influential, but this was a different Avant-Garde, with a different orientation.

The easiest, albeit simplified, way to explain this would be to say that the principal story of the 1920s was of an active struggle between the Avant-Garde painters and the artists of the anti-Avant-Garde that was gaining serious momentum. But the truth is, in the the early 1920s, Avant-Garde art was undergoing a crisis of its own, without any outside help. This could at least be said of those artists with high ambitions, engaged solely in the search for a universal language and the preaching of this new vision. Nobody really needed this, apart from the narrow circle of its creators, their adherents, friends and enemies from the same field. But now, being in demand was important. It wasn’t enough to simply work with your students at INKhUK and GINKhUK, one had to be useful somehow.

This situation gave birth to the concept of industrial art. To a certain degree, this was a replication of the Modernist utopia, which sought to transform the world through the creation of new forms for everyday things, and to save mankind by means of the correct kind of beauty. Everything, from clothes to dishware, had to be modern and progressive. This enabled art to justify its existence, as something applied and even useful. The Avant-Garde artists were now engaged in the production of Suprematist and Constructivist fabrics, porcelain, clothes, printing, books, posters, and photos. Among them were Lyubov Popova, Varvara Stepanova, Alexander Rodchenko, El Lissitzky, Vladimir Tatlin, and many others.

At the same time, Suprematist items, such as the dishware created by Malevich’s students under his tutelage, were in no way practical, and didn’t even strive to achieve usefulness. Malevich thought in universal categories, and in this regard his dishware, the so-called half-cups, were similar to his skyscraper projects for the people of the future. Nothing he did was for those who lived in the here and now. At the same time, Constructivist products were widely employed, being functional: the dishware could be used, the clothes could be worn, and the buildings were fit for work and leisure.

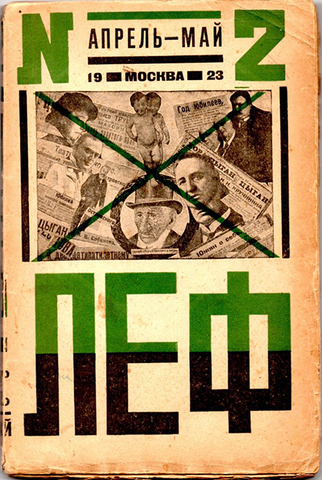

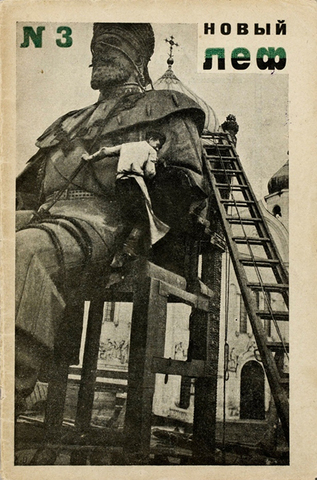

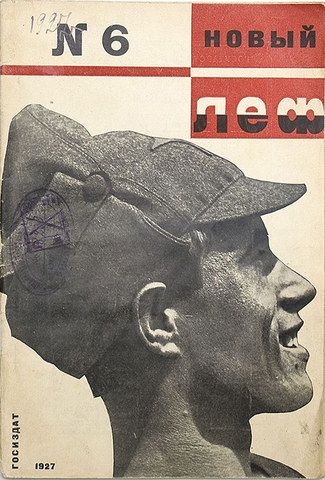

Ideological justification of industrial art was carried out by the LEF society, short for ‘Left Front’, and its publications, the magazines LEF and New LEF. This was a literary association, established in 1922, and its tone was set by Mayakovsky and Osip Brik. They were mostly concerned with literature, discussing the literature of facts and foregoing creative writing in favour of documenting reality, as well as fulfilling the social mandate and building a new way of life. But LEF also attracted a number of Constructivist artists and architects, such as the Vesnin brothers and Moisei Ginzburg. LEF was the foundation for the establishment of the Organisation of Contemporary Architects, known as the OSA group.

LEF was one of the extremes on the map of that decade’s artistic groupings. At the opposite pole was the AKhRR, the Association of Artists of Revolutionary Russia. Later, the group would lose one of the ‘Rs’ in its acronym, becoming the Association of Artists of the Revolution. These were the remnants of the Peredvizhniki movement, or the Association of Travelling Art Exhibitions, which had lost its relevance about 30 years prior, though it had continued to operate ever since, enlisting painters who dropped out of art schools. It wasn’t until 1923 that the Peredvizhniki association was officially abolished, and its members automatically became members of the AKhRR.

The motivating idea of the AKhRR was that Russia was experiencing a new period of socialist construction, and that art had to honestly record this new age, its characteristics, motifs, and events. The medium of expression was irrelevant here.

A small aside: there was a point in time when the Russian social media audience discovered one of the Association’s members, the painter Ivan Vladimirov. His exceptionally poorly executed paintings chronicled the first post-revolutionary years. The plundering of a nobleman’s estate. A dead horse being torn apart by people, because the year is 1919 and famine reigns. A landowner and a priest being put on trial, right before their shooting. People began reposting selections of Vladimirov’s paintings with comments like “I didn’t know that artists recognised all this horror in the first post-revolutionary years.” But what you have to understand is that the ‘horror’ in those paintings is the result of modern-day perceptions, while Vladimirov didn’t make any judgments. He was a dispassionate reporter who captured things that he saw – and he saw a lot. Plus, keep in mind that Vladimirov was a policeman.

So, the Association of Artists of the Revolution’s painting is the art of fact. As mentioned earlier, LEF defended the literature of fact. At a certain ideological level, the aesthetic opposites came together.

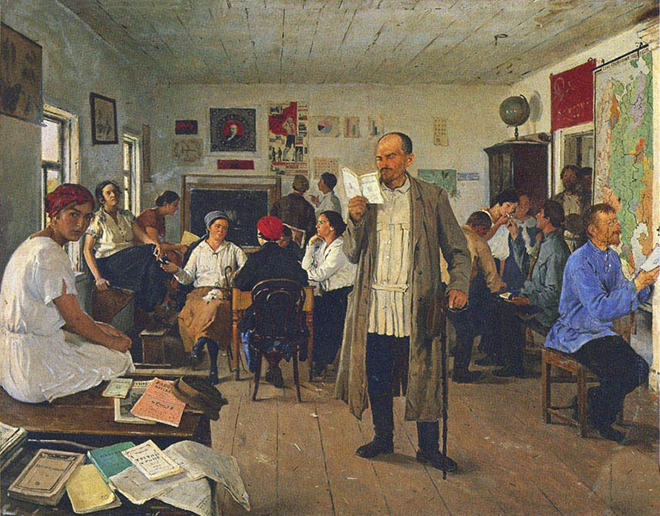

Or take another Association painter by the name of Yefim Cheptsov. One of his works is called Teacher Retraining. It depicts a room with some people, a couple of whom look like pre-revolutionary types. They are reading pamphlets, whose titles are legible – Third Front, Red Dawn, and Educating Workers. But here’s a question – why is it ‘retraining’ and not just ‘teacher training’ or ‘an examination’? The simple-minded painter was trying to use the painting’s name to convey an idea he wasn’t able to convey in paint alone – and he couldn’t have done it anyway, because the word ‘retraining’ implies a certain time depth. Instead, he took the word ‘retraining’ from one of the depicted brochures, failing to understand that he was not naming a book, but a painting. And this was something quite commonplace at the time.

The dull naive paintings by the artists of the early Association resemble the works of the very early Peredvizhniki period in their disdain for aesthetics. Early in the history of their movement, the Peredvizhniki, or ‘Wanderers’, had an ideological aversion to the very idea of beauty in painting. How could you speak of beauty, when there was evil in the world, which art had to denounce? The world was now in a state of revolutionary transition, but it was all happening so quickly and all of the events had to be captured, so who had time for beauty? The Red Army was winning, the peasant councils were meeting, infrastructure was being built. All of this had to be depicted to leave documentary evidence. The painters seemed to leave their paintings without any individual presence of themselves. Paradoxically, this departure brought the Association’s painters closer to mass-market industrial art and to Malevich’s anonymous students from UNOVIS who didn’t sign their paintings as a matter of principle.

A little later, in the 1930s, this programme became the foundation of Socialist Realism, whose credo was to “portray reality in its revolutionary development.” But even as early as the 1920s, the works of the Association’s painters resonated with many in the corridors of power, because their art was simple and easy to understand. The Association found its principal patrons among the military – the Red Army, the Revolutionary Council, and People’s Commissar Voroshilov himself. The painters worked in accordance with the ‘social mandate’, and this was even written into the Association’s programme. It was not considered in any way objectionable. We fulfil the relevant commissions, which makes us relevant artists, they thought. And whoever has a commission from the state, has the state’s money.

Looking between these two polar opposites – The Association of Artists of Revolutionary Russia and the Left Front – the array of artistic associations of the 1920s resembles a map of nomadic wanderings. People moved from one group to another, and there were so many groups it’s hard to list them all. We’ll mention just a few.

Some were formed by the artists of the older generation, those who had emerged before the Revolution of 1917. The Society of Moscow Artists, for example, was mostly made up of former Jacks of Diamonds such as Pyotr Konchalovsky, Ilya Mashkov, and others. Their manifesto defended the rights of regular painting, which had been denied by the industrial artists, so in this regard they were the conservatives. At the same time, they said that painting itself cannot be the same as before – it had to reflect the modern-day reality and to do it without ‘formalism’, meaning excessive concentration on artistic methods at the expense of a painting’s subject matter. Characteristically enough, even though it would be another ten years before the discussion of formalism led to purges against the creative classes, the word was already being used with a negative connotation. Amazingly, it was the former hell-raisers and trouble-makers who were employing it with this connotation. The fight against formalism was in line with the ‘soil-bound’ tradition of the Russian intelligentsia. The idea was that we Russians value the subject matter more, while the West experiments with forms. The Society of Moscow Artists appropriated the tradition of the so-called Moscow school of painting, which entailed the use of deep, heavy brush strokes, and so the former Knaves became an ideal fit for Socialist Realism.

Another association of old-timers – of those who once had exhibited their work with Mir Iskusstva, and the Jacks, and at the “Blue Rose” Symbolist exhibition – was the Four Arts community. This included Kuzma Petrov-Vodkin, Martiros Saryan, Pavel Kuznetsov, Vladimir Favorsky, and many others. It was called Four Arts because, in addition to painters, sculptors and graphic artists, it included architects among its members. Their manifesto proclaimed no single unifying programme, however, as this was a community of people who valued the individual above all. Overall, it was a very calm manifesto, practically ‘harmless’. Some ritual words were uttered about the new subject matter, but the main point was the necessity of preserving figurative culture. Many Four Arts members ended up teaching at the Higher Art and Technical Studios in Moscow and Leningrad, where they trained up a number of students who would create underground art free from any connections with the triumphant Socialist Realism.

Let us mention two other associations that weren’t very noticeable against the common backdrop of the time, but which give a good idea of the wide range then current. One of them was NOZh (translated as ‘knife’ in English), the New Society of Painters, which existed between 1921 and 1924. This was a youthful invasion on Moscow, mostly made up of Odessa painters, such as Samuel Adlivankin, Mikhail Perutsky and Alexander Gluskin. They only managed to hold one exhibition, but their paintings, especially those by Adlivankin, had a Primitivist style and comic inflection that was practically unknown in Soviet art. This was Realism, but with its own special tone, and it ended up as something of a missed opportunity in the history of Russian art.

Another group was Makovets. Its central figure was Vasily Chekrygin, who perished at the age of 25, leaving behind astonishing graphic works. This group was highly varied in its make up. One member was Lev Zhegin, Chekrygin’s closest friend, and an unappreciated artist himself.

Another was Sergei Romanovich, a student and adherent of Mikhail Larionov. Yet another one was Sergei Gerasimov, the future Socialist Realist and the author of the famous painting The Partisan’s Mother. The group was christened by the religious philosopher Pavel Florensky, whose sister, Raisa Florenskaya, was also a member of Makovets. Makovets was the name of the hill on which the Orthodox spiritual leader Saint Sergius of Radonezh had founded the Monastery of the Trinity at Sergiyev Posad.

The members of Makovets weren’t averse to the prophetic and planetary pathos of the avant-garde. They dreamt of an inclusive art that could unite everyone, and whose symbol they found in frescos. But since frescos were impossible to make in such a hungry and devastated country, all art had to be viewed as a sketch, as an attempt to approach frescos. Artists were making sketches for some unknown, but principal text about humanity, which led to remakes of Old Masters and an appeal to religious themes. This was obviously a very untimely kind of art.

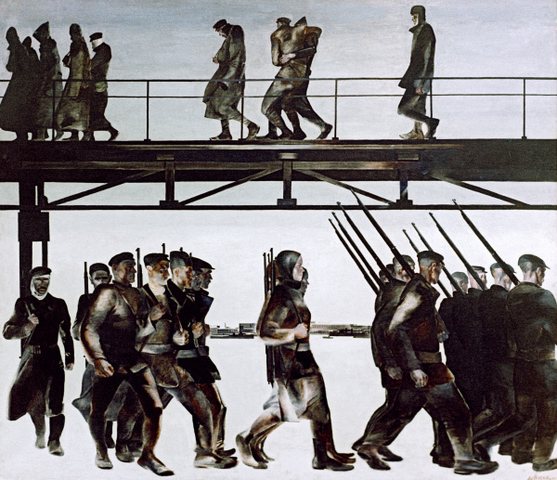

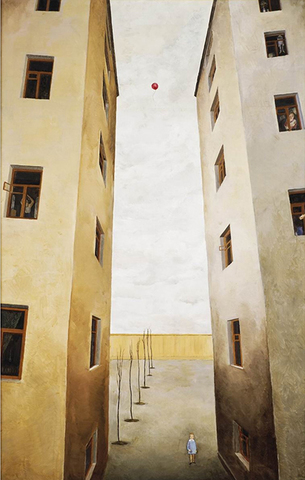

On the other hand, everything else would very soon end up left on the margins, too. By the second half of the 1920s, there were only two principal forces that opposed each other, but in the future they would have to work together, to shape the features of the ‘Soviet style’. One was the Association of Artists of Revolutionary Russia, and the other was the OST, the Society of Easel-Painters, referred to by contemporaries as “the most leftist of the rightist groups”. OST exhibitions presented the most discussed paintings of those years – The Defence of Petrograd by Alexander Deyneka, The Balloon Flew Away by Sergei Luchishkin, Aniska by David Shterenberg, and others. The Defence of Petrograd was a symbol of its times, a ‘two-storey’ composition, depicting the return of the wounded from the front in the upper register, and the march of the next group of Red Army fighters in the lower one. OST also counted Alexander Labas, Yuri Pimenov, Solomon Nikritin and Pyotr Williams among its members. Many of these had sprung from the Avant-Garde movement. Deyneka became the group’s poster boy, but left OST several years before its end. In Leningrad, OST had a counterpart of sorts, known as the ‘Circle of Painters’ society. Its figurehead was Alexander Samokhvalov, who was only a member for three years, but who painted Girl in a T-shirt, the period’s most life-asserting archetype. Characteristically, Samokhvalov’s girl would be used 30 years later as a style guide for the main female protagonist of the movie Time, Forward!, set in the 1930s. Even her striped t-shirt was the same.

The very combination of words – Society of Easel-Painters – was a declaration of an anti-LEF position. OST stood for easel painting and for painting as a whole, while LEF stood for mass production and design, for dishware and posters. By the mid-1920s, however, the Association of Revolutionary Artists was already more influential than the Left Front. The production utopia’s active period was over. The principal dispute was between OST and the Association, a battle over the future of modern art. Instead of the half-hearted imitation of nature and descriptiveness of the Association’s artists, OST was characterised by sharp perspectives, assemblage and outline brush work. Paintings became graphic and were reminiscent of monumental posters. The protagonists were invariably young and optimistic. They played sports and operated machines, and they resembled well-oiled machines themselves. OST paintings celebrated urban and industrial rhythms, orderly collective work, health and power. A physically perfect human being is spiritually perfect, and such new men and women were to be the citizens of the new Socialist society.

Of course, this wasn’t true for all of the society’s painters, just for its core. But in their intoxication with technology and orderly labour, the members of OST were, paradoxical as it may seem, close to the Constructivists of the LEF, the supposed principal target of OST’s programme.

And so, at the end of the 1920s, we witness the beginning of a new conflict. On one hand stood the pathos of OST, later transformed into Socialist Realism. This was all about the happiness of everything moving along – people, trains, cars, zeppelins, and planes. The perfection of technology and the beauty of collective efforts which lead to victory. On the other stood the completely opposite emotions, subject matters and visual instruments of Makovets, Four Arts, and others. Their paintings were quiet and static: indoor situations, low-key subjects, pictorial depth. People drinking tea or reading books, who seemed to live as if there was nothing outside their walls – certainly nothing grand or majestic. They lived in keeping with Mikhail Bulgakov’s words from the novel The White Guard: “never take the lampshade off the lamp.”

In the 1930s, all of this quiet art, with its lyrical and dramatic undertones, would be forced underground. The cult of youth and correct operation of machines would lead to large-scale parades and athletic celebrations, to the feeling of confluence with jubilant crowds. But this would only come in 1932, after the Central Committee of the Communist Party issued a decree “On the transformation of literary and artistic organisations”, abolishing all of these associations, and creating in their stead the unified Union of Artists. This heralded the next, ‘imperial’, period in the history of Soviet Art, which would last for over twenty years. The supremacy of Socialist Realism and the totalitarian ideology that nourished it.