Action Art: Performances, Actions, Happenings

From the Futurists to Pussy Riot: how hooliganism, self‑injury and strange behaviour became art

18+

Warning: You may find the illustrations to this lecture shocking or disturbing.

Action Art is currently a very common subject for discussion. The Pussy Riot trial, Pyotr Pavlensky’s performances and the antics of the Voina (‘War’) group are familiar to everybody due to the notoriety of their impact outside the field of art. This gives us all the more reason to try and make sense of the ways the art of action tries to break the boundaries of this field and how the outside world responds to these attempts.

Various terms have been used to define Action Art. The most popular are ‘performances’ and ‘artistic actions’, while ‘body art’ is less relevant, and ‘happenings’ or ‘environment’ actions are now completely forgotten. It is not always possible to tell apart a performance from an action or a happening from environment art. Similar forms of artistic expression have gone under different titles at different times. Dadaist and Surrealist scandals that involved shootings, fights and other kinds of aggression were not given a name as such, but they served as the basis for many subsequent movements, e.g. the happenings of the late 1950s and ‘60s. We will begin with them.

The American painter Allan Kaprow is believed to have established the concept of the happening. In his book, Assemblages, Environments and Happenings, he explained happenings as works of art that fill even more space than traditional art, up to and including the space of the entire planet. He sees them as a kind of theatre without a stage, for which an artist writes a script and preferably invites an audience. Ideally, everyone becomes a participant. The main purpose of a happening is the release of energy of an absurdist nature, as life itself is absurd, and a free and liberating stream should be revealed during this act.

Kaprow staged a performance entitled 18 happenings in six parts in New York in 1959. This absurdist show was held in three rooms; participants followed one another, squeezing orange juice, sweeping floors, shouting slogans, or just sitting on a chair. Since the happenings took place in different rooms at the same time, none of the spectators could either be involved in all eighteen, or even see them all.

Environment art is the same as a happening, but is less active in relation to the viewer. A viewer can enter the space of environment art without realising it. The white sculptured figures by George Segal, set up in New York, serve as a perfect example (so perfect that it can be found on Wikipedia). He created a Gay Liberation Monument consisting of white figures standing or sitting on benches, and passers-by can sit down next to them. Here, the integrated space of the living and the monuments, the space formed by reality and art constitute a piece of art. The main theme of Action Art is the flexibility of the boundaries between reality and art. In fact, this is the main theme of art in the 20th century as a whole.

The Russian artist Anatoly Osmolovsky carried out an interesting form of environment art. He named it “non-spectacular art”, as it was invisible; a viewer coming across this kind of art remains unaware of it. For example, an exhibition is taking place at Moscow’s Central House of Artists. At this venue, the pictures are often hung on dirty walls. What does Osmolovsky do? He takes an ordinary sheet of plywood, paints it a perfect white and puts it against one of the walls – as if the sheet of plywood had simply been forgotten here. It’s quite difficult to figure out that the space has become a work of art called Criticism of the State of the Walls.

Osmolovsky held leftist views. In one of his actions he referenced the Revolution by pulling out one of the loose blocks in a parquet floor, replacing it with a rickety board that was sticking up, as if after an explosion. This act symbolised the disruption in the smooth course of history brought by a revolution. The work was called Arise, Wretched of the Earth! Arise, Prisoners of Starvation! There was no note next to the floorboard and there was obviously no audience. A person entering the area of an environment artwork would not realise they had done so, as a very subtle, sensitive eye is required. Only the maintenance staff ‘acknowledged’ the work. Taking it for an act of hooliganism, they threw out the revolutionary piece of wood.

As mentioned above, it isn’t always possible to tell a happening from an environment artwork. For example, Claes Oldenburg called his 1961–1962 happening The Store a total environment, although by all accounts the sale of papier-mâché goods followed by dialogues with customers was closer to a classic Happening.

It was closer to classic happenings in particular since more recent works have lost both their cheerful lightness and their ecstatic unpredictability. The conjunction of life and art now occurs at a very mundane level. For example, the Thai artist Rirkrit Tiravanija became famous for setting up kitchens preparing Thai food and treating visitors at the galleries that invite him. He set up an apartment in one New York gallery where the audience could come for a visit and, if desired, even stay overnight.

But the word ‘happening’ itself is now unpopular, as the Surrealist line associated with unpredictable self-expression and the free outburst of energy is almost broken. The radical intentions that were more important than the execution of art in the 20th century have also been transformed. They really were radical – Breton said, for example, that the best artwork would be to open the window and keep shooting the crowd as long as there were bullets, while Malevich suggested burning all the paintings in the world and exhibiting the ashes. But their words never turned into action. The action began when performances and political actions replaced the happenings. The artist himself became a performer, at times putting himself and especially his body in danger.

Performances and actions are very close concepts, virtually interchangeable. But an action, in contrast to a performance, can be reduced to a pure gesture, a declaration. For example, in response to the invitation to participate in a portrait exhibition, Robert Rauschenberg sent a telegram saying that this telegram was the portrait itself, and thus agreed to participate in the exhibition. The artist Stanley Brown appointed all the shoe shops of Amsterdam to be his artworks. Such actions directly followed the proposal of the philosopher Marshall McLuhan that all human life be viewed as a work of art. The performance also suggests a specific action of the artist. It involves their own body, or, as is often the case, their own biography and memory.

Classic performance is an art that involves the body of the artist instead of a brush and canvas. Then the action itself, its documentation and the interaction of the artist with the audience become the artwork. The artist chooses the time and place of the performance in advance, he creates a script and envisages the reaction of the spectators; of course there is no guarantee that nothing will go wrong. We will discuss possible outcomes later and focus not on the audience’s reaction but rather that of society and the authorities.

Getting ahead of ourselves a little, it might be said that, over time, performance art has moved significantly away from its classical form. More precisely, this form very soon ceased to be the only one. So-called delegated performances came into being, for instance, in which the author acts as a curator, organising someone else’s body rather than his own. One form of delegated performance comprises mass public performances like the flash mobs currently popular in Russia, or the ‘Monstrations’, in the course of which people join May Day processions bearing absurd slogans.

The curator Joseph Backstein once staged an action at Butyrskaya Prison in Moscow that illustrates the aforementioned point. The prisoners repainted the walls perfectly white, and works of Moscow Conceptualists were hung on them. In several groups, various artists, art critics and VIPs were let into this prison ‘gallery’ and locked up there for an hour. ‘Free’ guests languished in captivity and were forced to empathise with the convicted, thus exposing the action’s meaning.

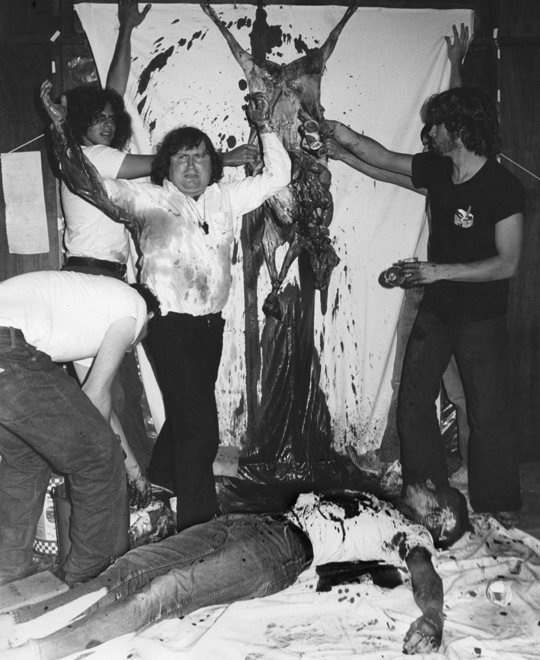

Let us now talk about the forms of performance where the artist challenges the strength of his own body, along with feelings, and even the physiological capacity, of the spectators. One example of this is Viennese Actionism, an Austrian movement of the 1960s, the most shocking performance art ever known to the public. The artist Hermann Nitsch appeared crucified and dipped his hands in the guts of freshly slaughtered animals while his assistants drank their blood; this orgy was supposed to refer to ancient rituals. Rudolf Schwartzkogler, an artist from the same group, had a medical instrument, similar to a corkscrew, screwed into his skull. The action only stopped when blood showed on the bandages.

Schwartzkogler, more prone than any other of his fellow artists to self-destructive behaviour, fell out of a window, most likely in suicide. Many believe that he was recreating the famous leap into the void of Yves Klein, the only difference being that Yves Klein did not actually jump into the void – it was photo editing. Before committing suicide, Schwartzkogler performed a shocking action, allegedly cutting off his penis piece by piece. He didn’t actually do this, though: the action, and a series of photographs that was left of it, were staged. There was a rumour that Schwartzkogler jumped out of the window due to the fact that people believed he had in fact performed this self-mutilation.

This is a very important subject for Action Art. What happens during the performance is one part. Another is what is documented. And yet another is the way in which the performance spreads in rumours and the news, and how it remains in people’s memories.

The Viennese Actionists had a major influence on the subsequent history of performance, including on Russian artists. Viennese artists sacrificed animals; and then Oleg Kulik handed out meat from a freshly slaughtered pig in the Regina Gallery in Moscow, during the Piglet Hands Out Gifts performance. The Viennese actionist Günter Brus had masturbated beside an Austrian flag while singing the national anthem (for which he would be taken to jail). And then Alexander Brener masturbated from a diving board at the site of the dismantled “Moscow” swimming pool. The American actionist Chris Burden had crawled on broken glass in his underwear. (and would become famous after his performance Shot, during which he asked his assistant to shoot him in the arm). And then the Russian actionist Elena Kovylina walks barefoot on broken glass, offering caviar to exhibition guests. Liza Morozova performs the similar action Underwear walking along a path of broken glass in her nightgown while she reads her childhood diary, thus working with the personal, most intimate and painful.

We have now come to yet another dimension of performance, which is called ‘Living Art’ in the West, that is, the art of life, when the art and life of the author become one. Most often, such a fusion of life and art is heroic. Five performances of the Taiwanese artist Tehching Hsieh serve as the most incredible and truly heroic examples. Each of them lasted for a year. The first year Tehching Hsieh spent sitting in a cage. He had food and water, but he forbade himself to speak, read, write, and watch TV. He was only allowed to think and, so to speak, study himself. Spectators were granted admission to him once or twice a month. Over the next year, he documented his presence in an apartment with a clock and a camera shot every hour, thus preventing him from being able to sleep or leave the apartment for more than 59 minutes. Over the third year, he forbade himself to enter any indoor space, or even shelter from rain under awnings implying that he lived in the open air. This performance was interrupted for 15 hours: he was arrested by the police and was desperate since the police office was indoors. The fourth year was the scariest: it was a performance for two. Another participant, Linda Montano, was tied to the artist with a long rope, and they were inseparable for a year. Their relationship was devoid of sensuality: they were not allowed to touch each other, but each of them depended on the other. It is known that they quarrelled a lot and this year was extremely hard for both of them. Finally, for his fifth year, Tehching Hsieh swore not to talk about art, nor read about it, deal with it or look at it. After that he pledged to make art without an audience, not showing the results of his work for thirteen years.

Living art can also often take painful forms. One of the most striking examples of self-torture belongs to the experience of the Russian artist Oleg Mavromatti. His most famous action Do Not Believe Your Eyes served as a prelude. The artist was crucified on a cross, with the phrase “I am not the son of God” cut into his back with a razor, after which he was accused of violating the blasphemy laws and forced to leave the country. Upon settling in Bulgaria, he made his most frightening performance. This was called Ally / Foe and involved the risk of death, live on air. For one week, an online vote was held to determine whether Mavromatti should live or die. When the number of votes for his death reached certain numbers, the artist received an electric shock. If the votes for his death exceeded those for life by 100%, the electrical impulse would kill him. Fortunately, this did not happen.

The risk that the artist takes on is very important in the heroic version of performance. Marina Abramović is a key figure here. She had a series of performances under the title Rhythm. In 1974, during the six-hour long performance Rhythm 0, she was locked in a gallery with the public and seventy-two objects, among which were some harmless ones, like grapes and bread, and various stabbing and cutting weapons, and a gun. The viewers were free to do anything with these objects and her body. So they did: her dress was cut, she was stripped, stabbed, slashed and almost killed – one spectator took the gun, but it was whipped away from him. In contrast, you might recall Yoko Ono’s performance, held in 1964 as part of the “Fluxus” movement. Each member of the audience could cut off a piece of her dress, but her life was not in danger. In just 10 years, artists had upped the ante of danger in performance art significantly.

Not only one’s health can be threatened but also one’s social life. It is hard to say what outcome the Russian action artist Avdey Ter-Oganyan expected when he held his Young Atheist (aka Pop Art) performance at the Manège Exhibition Centre. It was said that he was chopping up icons with an axe, but he was actually chopping up cheap reproductions from Sofrino. Nevertheless, he had to leave the country due to criminal prosecution.

In some cases, art has attempted to completely erase the boundaries between life and itself, often receiving life’s answer in the most unexpected ways. The classic performance artist Bas Jan Ader studied the poetics of failure in his work. He would ride a bike and then fall with it into an Amsterdam canal. He might climb a tree or a roof only to then fall down from it. His last performance bore the name In Search of the Miraculous. Its central part constituted sailing from America to England on a tiny boat that wasn’t suitable for such a journey. He spent two years planning and documenting his preparation in full, arranging for an exhibition with a London gallery on arrival. In the end, his vessel was found, but Bas Jan Ader’s location remains unknown to this day.

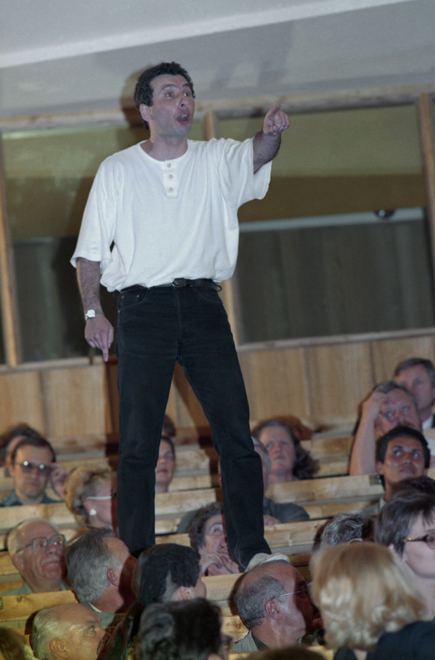

Let’s elaborate on the poetics of failure. The Russian actionist Alexander Brener focused on the same idea. Many of his artistic actions spoke of failures. He failed to have sex with his wife at the Alexander Pushkin monument in the centre of Moscow, as it was too cold. He failed to challenge the president to a boxing match on Red Square. Brener came to the fight, but Yeltsin was nowhere to be seen. And the most obvious example is the huge 1994 exhibition at the Central Union for Artists, entitled “The Artist Instead of the Work of Art”, dedicated to Actionism and its documentation. Brener, wearing nothing but transparent tights, showed up at the opening of the exhibition and cried out: “Why was I not invited to participate in this exhibition?” Even the guards didn’t rush to seize him. Thus Brener was, after all, rightfully presented at the exhibition on Actionism. Secondly, he acted out the image of a loser who is always hurt and whose works are not being taken seriously enough.

Even Brener’s most internationally well-known artistic action is based on the theme of failure. In 1997, he drew a dollar sign on a Malevich painting in Amsterdam’s Stedelijk Museum. This got him put in a Dutch prison, just one of his numerous failures. This work was a reference to a very well-known piece by Robert Rauschenberg, called Erased de Kooning Drawing. Rauschenberg had partially erased a drawing by the famous Dutch-American artist Willem de Kooning, and presented it as his work. Thus raising the question, who was the genuine author of the palimpsest? Was it De Kooning, the original artist, or Rauschenberg, who exhibited the half-erased drawing? Brener’s and Rauschenberg’s intentions were similar. Brener was in a way appropriating the Suprematist painting with his dollar sign. If modern art denounced hierarchy as much as it claimed to do, Brener would be recognised as the author of this work. In effect, Brener’s and Malevich’s equality as artists was not even in question, and Malevich’s work was safely restored.

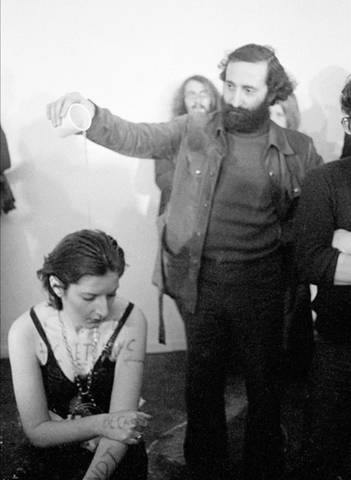

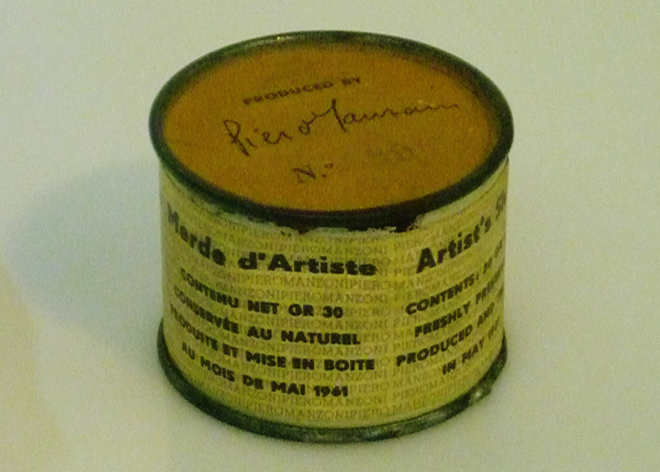

The Italian artist Piero Manzoni was much more successful at appropriating different objects and people in his work in the 1960s. He had shaken the public many times before his death at the age of 30. He sold sealed tin cans with the label “Artist’s Shit”. Manzoni’s Artist’s Shit cans were sold for considerable sums of money, and are now kept at major museums and private collections. Since their purchase in 1961, the cans have been preserved for many years, and still no one knows what’s really inside them. His second work of this kind was called The Artist’s Breath: Manzoni inflated balloons and sold them. In both his actions he simultaneously mocked the romantic image of the artist who creates only the sublime, and consumer society, which is prepared to buy anything under the guise of art. He also sold his own fingerprints, painted on living people, and declared several people to be works of art, including Umberto Eco, and built a pedestal which enabled anyone that mounted it to become a work of art.

Oleg Kulik, also known as the Dog-Man, is an artist whose works comprise shock, danger and laughter, all at the same time. His performances largely date back to the Cynic philosophers of ancient Greece, to the mediaeval traditions of the Russian holy ‘fools for Christ’, and even to Viennese Actionism. They refer to a 1968 performance by Valie Export who horrified passers-by by walking Peter Weibel on a leash. Kulik always acknowledged that his performances were a replication. Joseph Beuys once held a famous performance called I Love America, America Loves Me; Beuys arrives in America, but doesn’t set foot on American soil. He is put in a cage with a coyote straight from the plane, and they live in this cage together. Kulik responded to this action with two of his own. The first one was conducted in 1996 in Berlin, and entitled I Love Europe, but She Doesn’t Love Me Back. The naked Kulik stood on all fours and barked, surrounded by 12 German shepherd dogs, barely restrained by policemen, 12 symbolising the number of stars on the flag of the newly formed European Union. The second action was called I Bite America, America Is Biting Me. In 1997 the Dog-Man arrived in the USA wearing a collar and immediately started violating US social norms. He lived in a cage at an art gallery, the door of which was open, allowing him to crawl out and harass women visiting the gallery. He claimed they were only too happy about it. Travesty and the parody of high art (Beuys, in particular) were connected in the case of Kulik with playing out ‘Russian-ness’, with all of its pseudo-patriotic and political connotations. Russian means wild and unpredictable (it can bite), but free because of it; it is closer to nature than to civilisation; it is meant to astonish the West as well as to frighten it.

The political aspect is an important component in today’s performative practices, which brings us to Pussy Riot. Pussy Riot is a group of young women who filmed themselves performing a protest song near the altar of Moscow’s Cathedral of Christ the Saviour. This began as an act of art but turned into a political case when the authorities intervened. The result was tangible; the women were sentenced to two years in prison.

This ambiguity in affiliation – to art or to politics? – is very characteristic of political performance: Pussy Riot have proved their involvement in an old established tradition.

In the 1940s and ‘50s, a leftist group calling themselves the Lettrists operated in France (the Situationist International and the 1968 uprising would eventually emerge from this group). In 1950, a group of Lettrists slipped unobserved into Notre Dame during the Easter service, which was being broadcast live on TV. They tied up and stripped the priest, one of their members named Moore put on his clothes, went to the pulpit, and from there announced that God was dead and that the Catholic Church was evil. They were arrested, but soon released – a two year jail sentence certainly being out of question.

Performances with a strong political component have also been quite ambitious. In 1972, Joseph Beuys, serving as the Head of the Art Department at the Düsseldorf Academy of Arts, tried to carry out a student revolution. He organised a group of students who were denied enrolment in his classes; they barricaded themselves in the building. The police were called, everyone was forced out, and Beuys was kicked out of the Academy – he then captured this event in his work entitled Democracy Is Merry.

Russian art was familiar with political actions long before Pussy Riot and Pavlensky. In 1975, in Leningrad, Igor Zakharov-Ross burned a dummy of a Soviet passport. The performance was entitled I Want to Go to America. Two years later, he staged a performance in the suburbs of Leningrad under the title Enclosure; he built a cramped paper tent, into which the audience was invited. Then he set fire to the tent, and it took to the air – he literally played with fire. Shortly thereafter, Zakharov-Ross’s citizenship was revoked and he was ordered to leave the USSR.

It is impossible to list all the significant figures of Russian Actionism in just a short lecture. But we have to mention Pyotr Pavlensky, who continues the tradition of Viennese Actionism and embodies Living Art in its ultimate manifestation. His protests are well known: the sewn-up mouth (A Seam in Support of Pussy Riot), barbed wire wrapped around his naked body (an action entitled Carcass), the scrotum nailed to the cobblestone paving of Red Square (entitled Fixation), his sliced off earlobe (Separation), and the notorious setting fire to the FSB building’s door at Lubyanka (Threat). These actions have the political in them to an incredibly high degree.

And so, we have seen that Russian Actionism has an interesting history and background. It begins in the era of the Avant-Garde, but the actions most often remembered are usually quite harmless. Mayakovsky’s yellow jacket, the Futurist makeup, and Malevich with a wooden spoon in his buttonhole and Kruchenykh with a carrot in his were just a little slap in the face of public taste. In short, they were not very shocking. At the same time, a real performer who called himself ‘Life’s Futurist’ lived and worked in Russia. His name was Vladimir Holtzschmidt and the Futurists did not welcome him as one of their own. They treated him with contempt, believing him to be more a circus entertainer, if not a circus clown, than a man of the new art. Holtzschmidt gave lectures on Futurism and read his monstrous Futurist poetry at his performances. One could also break boards against his head; both his audience and he himself engaged in these acts. He is also known for walking down Petrovka Street naked with two assistants, holding a board saying “Down with Shame”. The history of Russian Actionism is a progression from the first “Life’s Futurist” to the fierce Pavlensky.